🌻 how to party like an AI researcher

a NeurIPS 2025 scene report

it’s weird to see tech reporters posting about attending NeurIPS - surely, they must have something better to do than chase gossip at an ostensibly technical conference

— Peyman Milanfar, Distinguished Scientist at Google, Fellow of the IEEE

In 1987, roughly 600 renegade physicists, neuroscientists, and engineers gathered in Denver, Colorado to discuss experimental computer architectures based on the human brain. At the time, “neural networks” were still a fringe research area: brittle rule-based systems still dominated the AI mainstream, while backpropagation had only just been reintroduced in 1986. This was the first Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.1

Today, NeurIPS is over forty times larger, and looks less like a kooky pirate crew than a cornucopic symbol of the swelling field overtaking CS departments, the tech industry, and the US economy too. A record 26,382 people have registered for NeurIPS 2025, nearly all in San Diego, with two tiny satellites in Mexico City2 and “virtual” attendees. Keynotes from field titans—like Ilya Sutskever’s “peak data” talk last year—can shift research trends overnight; winning a “Best Paper” award can make a junior researcher’s career.

But all this is a fig leaf for hanging out. On the ground, NeurIPS feels like one long holiday party, where grad students from around the world break from tuning their hyperparameters to drink champagne on some tech company’s dime. And the gap between NeurIPS-as-research-showcase and NeurIPS-as-industry-party is larger now that so much frontier AI research happens in closed labs, while university students toy with smaller models and scrounge for compute. (Reading Google’s published papers is arguably a better way to discover what they’re not working on—anything going into Gemini training won’t be released.)

In the days before the conference, party invites—not GPU hours—briefly become the most valuable currency on the market. Most parties are hosted by companies trying to recruit top academic talent. There are also socials based on affinity groups, hosted by VC firms, for existing employees at a given company, and even more exclusive unlisted dinners. Conversations fill with “What are you up to tonight? Are they checking the guest list? Can you get me into X if I get you into Y?”

Someone forwarded me a spreadsheet containing 155 different parties and attached Luma links, arranged meticulously by hour and day. Events had titles like “Cafe Compute” (hosted by Cerebras, an infrastructure company), “Barry’s With Builders” (hosted by Bain Capital Ventures), and “Centific x Reinforce Labs NeurIPS 2025: Agentic AI: Organizational Automation vs. Personalization at Scale” (???). Registrations ask for your name, LinkedIn profile, and other legible signs of market value. Corporate sponsors want the highest ratio of researchers to riffraff—and specifically top researchers from top institutions—to signal that they’re doing serious intellectual work and not merely a scene.

Here, I am definitely the riffraff.

TUESDAY

Everyone at Gate 32, Oakland International Airport, is here for the same reason. The man next to me hunches over his laptop, tweaking a last-minute slide deck, while a group of skinny Chinese guys in hoodies and joggers jabber in Mandarin. “It was the same flying to Singapore for ICLR, except it was first class for frontier labs, and economy for the rest,” one passenger remarks.

Once landed, I head straight to the Hilton for official duties: I’m here to host a batch of podcasts for the AI media collective SAIL. We set up a full podcast studio in a meeting room across from the convention center—complete with cameras, lights, and mics—and invite any researcher to grab a 10-minute Calendly slot to be interviewed about their work.

Lex Fridman is the only person who shows up during my first shift. He did not need a podcast recorded, but stopped by to say hi to his friends. He’s trying to get back into research now, working on some robotics papers, here to meet academics. At NeurIPS registration, he declines to wait in the VIP line, which I respect. His badge reads “MIT.”

A SAIL team member hands Lex three golden tickets to bestow on any researchers he is especially impressed by. Each metallic ticket, sealed in an elegant black envelope, was one admit to a yacht party they’re throwing Friday night. Walking back to my hotel, I’m accosted by a club promoter waving around his own glossy flyers, and am hit with a sense of deja vu.

WEDNESDAY

San Diego’s Gaslamp Quarter is distinctly Southern Californian, with wide streets and palm trees sprouting into the skyline. But the blocks around the conference feel more like San Francisco: hordes of bespectacled tech workers in branded backpacks, routing around homeless people passed out on the sidewalk.

I record back-to-back SAIL podcasts on Wednesday morning. My interviewees range from reticent researchers to bombastic founders. You can tell who’s who in a millisecond: the startup guys have firmer handshakes, louder voices, practiced lines. Even if they began in academia, they’ve now been trained by countless enterprise sales pitches and VC meetings. By contrast, the researchers tremble from nerves and speak in four-syllable words. When I ask “Is there anything you disagree with peers in your field about?” they reply with “Can I skip this one?”

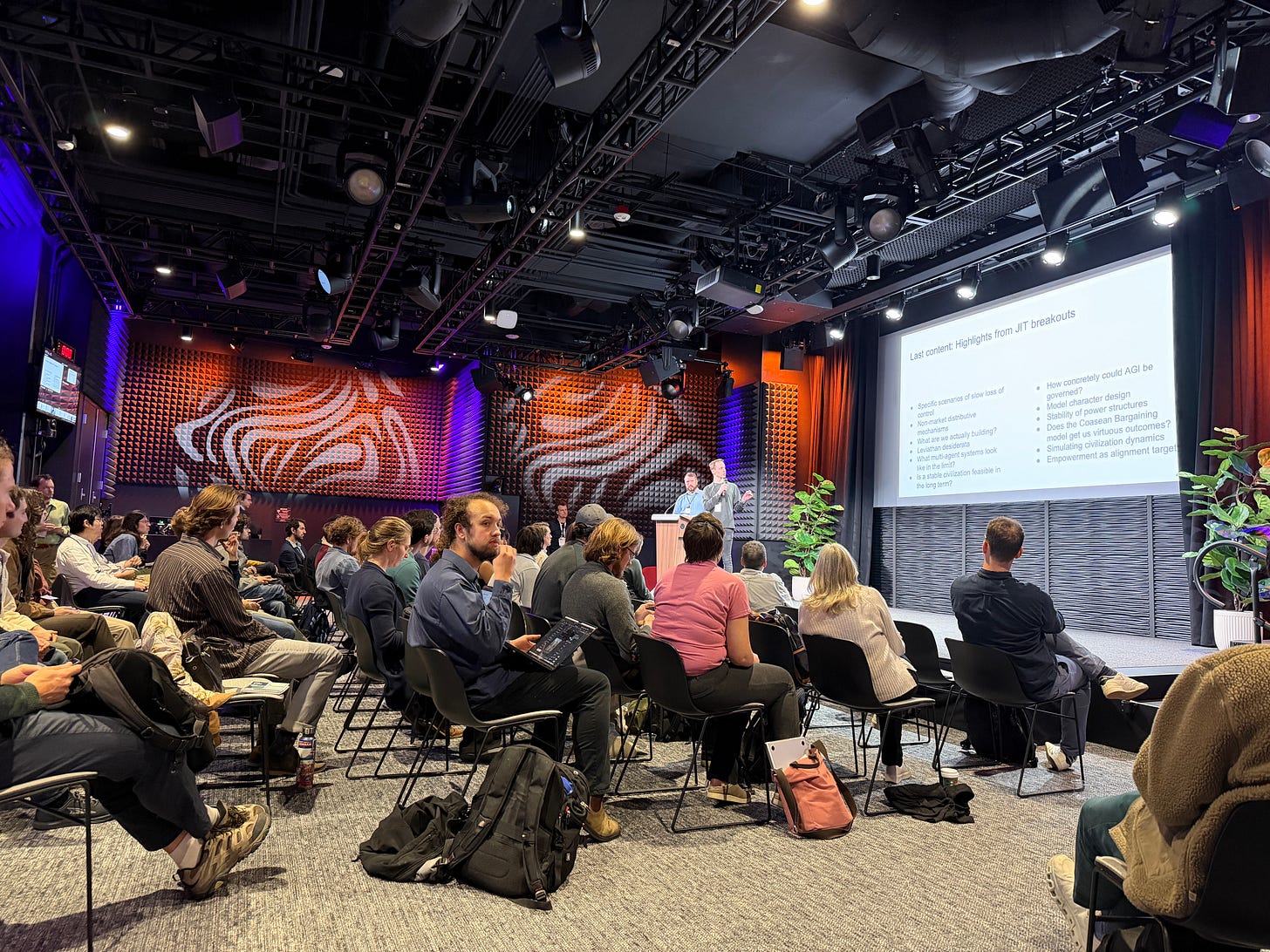

Afterwards, I walk to a side workshop I signed up for called “Post-AGI.” The premise is: What if we get superintelligence and don’t instantly die? It aimed to challenge people usually preoccupied with averting AI doom to imagine the new political and economic structures necessary for a post-AGI world.3

There are talks on UBI, AI personhood, and “Cyborg Leviathans,” i.e. a world where AI replaces most human institutions. Attendees ranged from longtermist philosophers like Will MacAskill and Nick Bostrom, staff from various EA and EA-adjacent nonprofits, and researchers at the frontier labs.4 Most of NeurIPS is nerdy but normal: filled with earnest academics with narrow technical fixations. But this workshop felt like I’d been teleported to Berkeley and Oxford at once.

I jump into a 20-person session with the UVA economist Anton Korinek, who’s a bit of a radical in his discipline for entertaining the plausibility of hyperbolic GDP growth from transformative AI. He is soft-spoken, angular, and has a thick Austrian accent. At one point, stumbling through the beginning of a sentence, he says “I’m starting to run into nonsensical token generation in my reasoning chain.”

When the room splits into breakouts to talk redistribution, two men in mine challenge Korinek’s assumptions instead. He’s too conservative, they think: “I expect GDP to double every day.”

As far as I remember, these folks’ counter-argument went something like this: After superintelligence, we should expect that human wages will go to zero but capital to infinity. There will be a brief transition period where we have cognitive superintelligence but not advanced robotics—so we can all work as the AI’s meat-slaves—but after that, AI will recursively self-improve, tiling the galaxy in space factories, and rendering human labor useless.5 But this participant didn’t think this was a future to fear: “The vibe of this conference is oh no, what if humans lose control over the future, and I’m more like, oh no, what if the monkeys are still running things?”

“So how did you estimate one day as the GDP doubling rate?” I ask.

“Just vibes,” his friend replies. “Like, that’s how fast bacteria double.”

To its credit, the Post-AGI workshop is the one room of AI people who believe in politics: they recognize the difference between money and power, between bosses and workers, between meeting your material needs and having a say in your society’s future. Even if some of their timelines seemed insane and some speakers were too into a One World Government for my liking, they are at least willing to say that powerful AI may concentrate power in the hands of corporations, super-charge the abilities of surveillance states, and/or eliminate significant numbers of jobs. And maybe, maybe this was all important to plan for.

The hottest party that night is Cohere’s “Holiday Hangar.” It’s located on a giant historic aircraft carrier, the USS Midway, that they decked in Christmas lights. I’m not early enough to make it, but am told by “sucker for American power” Jordan Schneider that the execution was underwhelming: “The action wasn’t on the dance floor but around the Jenga table, where I played the most careful game of Jenga of my life, easily doubling the original height.”

While loitering by the entrance with a friend, I run into a reporting source, an old coworker, and a guy who went viral for shitting his pants. Then, another journalist—the real kind—shows up and starts asking questions. What my conference takeaways are, what Elon’s up to, which OpenAI employees we know. He’s here to “get more technical,” which is journo-speak for “scavenging for scoops.” I suggest we all escape the corpo happy hour circuit, but he reroutes us to an Nvidia event, where they give us branded beanies then shoo us away.

Finally, I persuade everyone to just go to a bar. We can buy our own drinks.

THURSDAY

My podcasting skills improve as I learn how to dumb the interviews down. I learn about diffusion models and drones that detect human screams and RL environments and theory of mind. Lots of multimodal, lots of new benchmarks, lots of reasoning this and continual learning that. People reference open-source models like Olmo and Llama, names I rarely hear in the Bay Area scene. These folks are also sunny about the AI future in a sweet, naive way: I want AI that helps us connect, learn, have deeper conversations. Maybe playing with neural nets will help me decode how humans work, too.

Later, Nathan Lambert texts me that the Autism Spectrum Disorder Foundation is tabling outside the conference. This strikes me as too good to be true, but sure enough, a little green booth is stationed between the train tracks and the Midjourney ice cream truck. I walk up to compliment them on the bit.

“Are you guys always here?” I ask.

“No, we’re not,” says the staffer. “We saw a lot of people so figured it’s a good place to be. But people keep shouting great location! at us and we don’t know why.”

It dawns on me that there is no bit—only a fully earnest effort to fundraise for art classes for autistic kids. I awkwardly try to explain the joke (“it’s a stereotype about there being a lot of autistic people in AI, but, um, in a positive way”) but it’s hopeless. The upbeat man at the booth only seems more confused.

By now I still haven’t been inside the actual conference. Every room, every hall is overwhelmingly large. There are escalators that go to ballrooms that go to terraces that go to cafeterias.

I stumble into the expo hall first. Alongside the obvious candidates (Google, Microsoft, Meta, Tesla) were quant firms (HRT, Jane Street), a surprising number of Chinese companies (Bytedance, Kuaishou), Gulf AI institutions (MBZUAI), and a big Renaissance Philanthropy booth. My initial reporting strategy is to take notes on which companies had the longest lines, until I realize that it’s “whoever booked a free coffee cart.” It’s a funny sight: hundreds of people interviewing for $500k/year roles, willing to wait 30 minutes backpack-to-backpack to save $5 on a cappuccino.

The poster hall is emptier, but just as overwhelming. Nathan mentions that there are all kinds of minor grifts to make your work stand out: stealing a purple “ORAL” flag to pin on the board, bringing friends as audience plants to seed a crowd, startups turning empty slots into guerilla billboard ads. Some posters advertise “Seeking Internships for Summer 2026.”

Most AI PhDs are making less than $50k a year, while peers who drop out to join the private sector can earn 10 times that. Meanwhile, Trump’s cuts are jeopardizing already-scarce academic opportunities. Some quietly resent the closed labs while applying for jobs. Given the “bitter lesson”—that more compute, not cleverer algorithms, is the primary driver of AI progress—you increasingly need industry-scale resources to do ambitious work.

Later, I meet friends at a company happy hour with a jacked, tattooed bouncer manning the guest list and a strict no-reporting rule. During some highly classified cheese and fraternizing, we hear that some Berkeley PhDs were throwing a real house party—Airbnb rental, no sponsors, hosts with “frat star” experience. We book an Uber and head over.

It’s one of those Airbnbs that’s designed for debauchery: there’s a dartboard, foosball table, ample patio nooks, block letters spelling B-A-R over the stove. But the vibe is all wrong. The overhead lights shine bright, and none of the drinks are open: not the Angry Orchard, nor the White Claw, nor the bottles of Fireball and wine. The background music is relaxing and slightly Christmassy. Most people keep their conference name tags on, which they unsubtly glance at before engaging in conversation. As circe wrote, “A conference is probably one of the few places in the world where a man will experience the “hey, eyes up here” phenomenon.”

The whole setup and its amateurishness piss Jordan off. He starts flipping off light switches and taking over the Sonos. He then grabs one of the grad student hosts for a stern talking-to: “Hey, do you live here? Text everyone now and tell them to BYOB. There’s not nearly enough for 500 people.”

I try to make conversation as the room fills: with an Italian researcher baffled by SF’s social culture, a London-based professor who left Google DeepMind when they closed off their research, a junior VC wearing a black HACKER hoodie, and way more Meta interns than makes sense given their output. When a group of Asian girls walk in, a white man nearby mutters, “Dude, there are so many spies here.” It’s time to go.

FRIDAY

The big boat party is tonight, and everyone is stressed about the guest list. Model Ship 2025 has four Substacker cohosts (Jordan, Nathan, Dylan Patel, Latent.Space) and three corporate sponsors (Cisco, Decibel, Lambda). Each cohost has their own list of invitees, but NeurIPS attendees are notoriously flaky, so they need a backup because nothing’s worse than being stuck for four hours on an empty boat. But that’s the problem: who do you add? Some vet for Twitter followers, others for employer (frontier labs on top), others for “a love for life and a sparkle in their eye.”

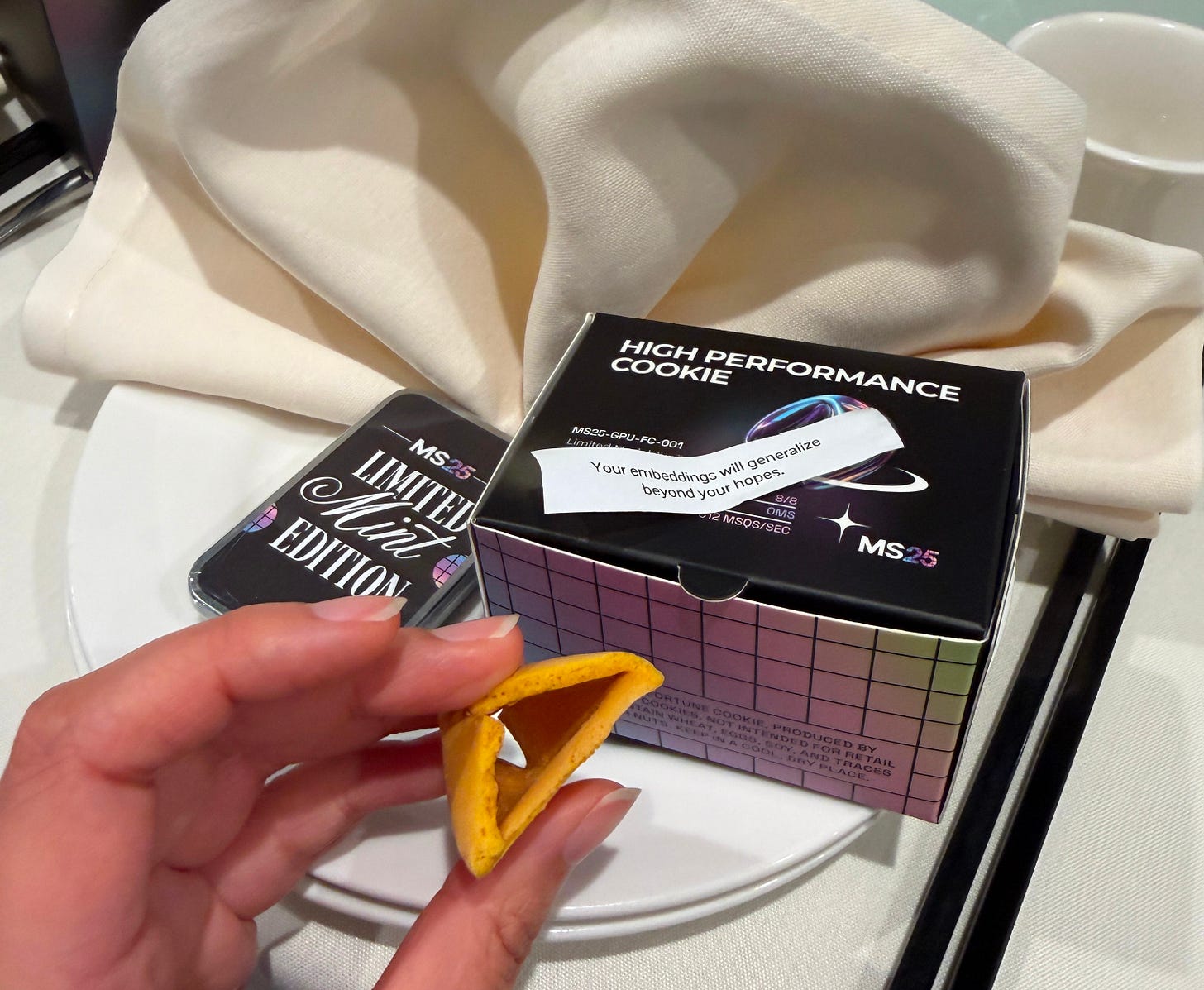

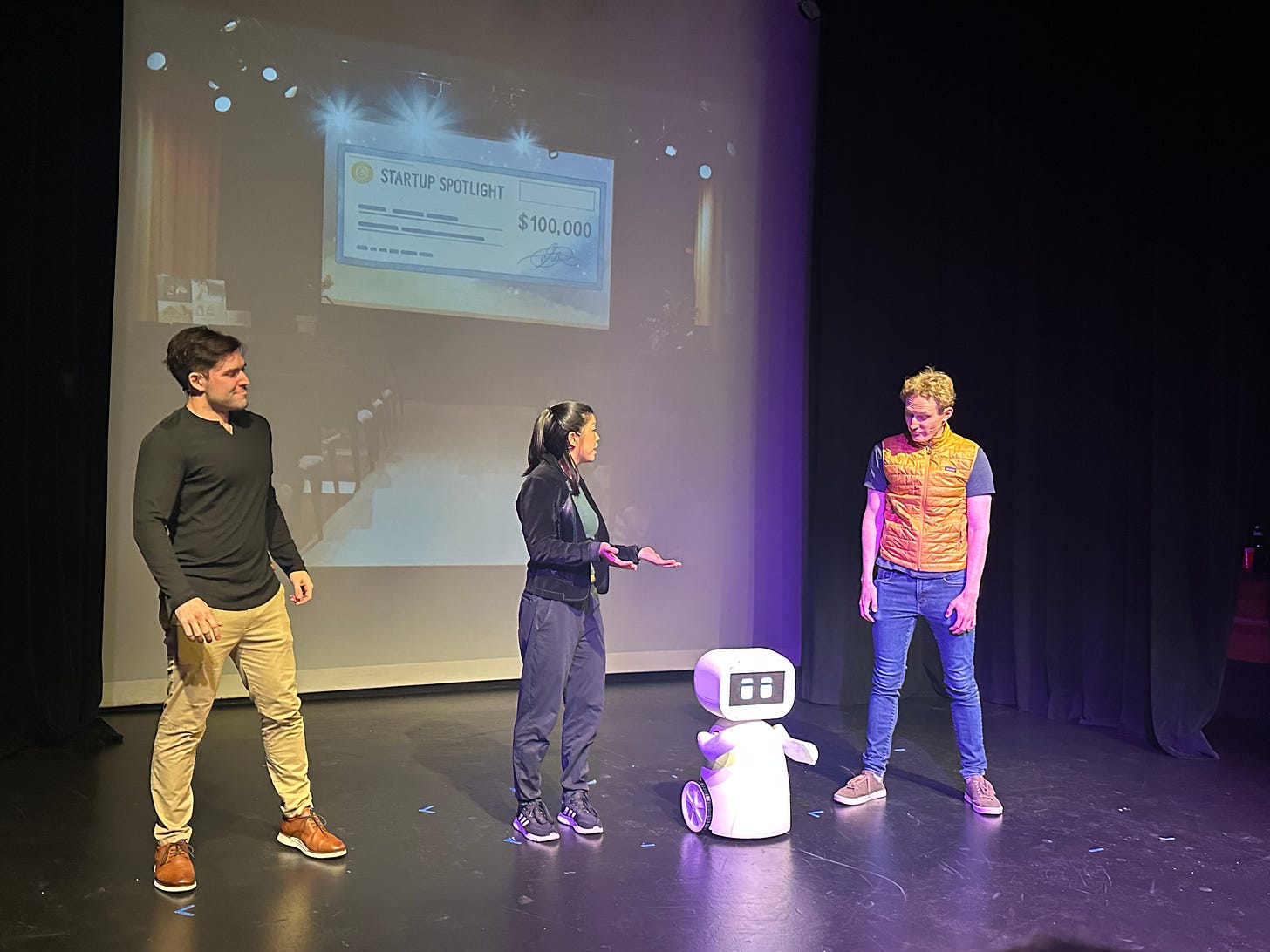

The fussiness exhausts me before the party even starts. But it’s hard to stay mad when you’re sipping champagne on a triple-decker yacht with views of the whole city blanketed in Christmas lights. Waiters walk around with platters of chicken skewers, cocktail shrimp, and mini beef wellies. There are three bars and tables decked out in clever swag: fortune cookies in boxes pretending to be GPUs, custom postcards based on 1960s Maoist science propaganda, metallic Shoggoth stickers; but also captain’s hats and neon sunglasses and classic spring breaker attire. An interactive art piece by Leo Chan, a burned-out-SWE turned artist, takes a photo of each attendee, then merges them into a single “average face.” We learn that the average AI researcher is a 30-year-old wasian man.

I team up with a VC at Andreessen Horowitz to play a custom game of AI Guess Who, where the stock faces have been replaced by GPT-generated illustrations of AI luminaries. There’s strategy to it: Don’t ask “Are they a woman?” because there are only four on the board. “Do they have glasses?” is the closest to a perfect starting question. When we switch to hard mode, which prohibits appearance-based questions, I go for career history instead: Do they have a PhD? Were they an immigrant? Have they ever worked at Google/DeepMind/GDM? Meanwhile, I quiz the VC on how she determines which academics make good founders: “I determine if what they really want is unlimited compute, which means they should just work at a big lab. The best have a specific vision for AI that all the current labs are missing.”

But that was as close to shop talk as I got while at sea. Maybe it was the fastidious guest selection, maybe the relief of a Friday, maybe the ever-flowing drinks, maybe being run by media and not startup people, maybe the DJ who played nonstop white people wedding hits after 9pm. People did shots and shrooms; they PDAed with strangers; they flailed their limbs and blew bubbles to Gasolina, Mr. Brightside, and Taylor Swift; they finally took off those horrible fucking name tags. It wasn’t until three days later when I realized, whoops, I must have signed a photo release. Hope those never get posted.

After returning to land, I follow a couple OpenAI and Anthropic employees to an after, which turned out to be the time-honored tradition of sitting around a fireplace trading inter-lab gossip. They were flying back for a big rationalist solstice party in Berkeley tomorrow, but not before seeing the pandas at the San Diego Zoo.

SATURDAY

More workshops and socials happen over the weekend. Jeff Dean mogs everyone on 7am runs. Lily Ottinger hits up a SF-based karaoke crew—one virtuoso is a co-creator of the excellent Silicon Valley: The Musical, which he described as “The Book of Mormon for AI safety.”6 There’s a Claude Code meetup and a YC party. Others take the day off to go to the beach.

I’m not doing any of it. It’s 10am when I wake up in my hotel room; my calves are sore from dancing and Zbiotics has only dampened my hangover halfway. I polish off my seventh fish taco and book an Uber to the airport.

Before coming to NeurIPS, a PhD friend based in Montreal told me that she usually sees the conference as an opportunity to learn “what the crazy SF people are up to.” That explains why I found it all fun but surprisingly tame. It felt more like a way for Bay Area companies to lure in the world’s best researchers—if you join us, you’ll be regaled like this every week—than the NeurIPS of yore, when AI still felt like one giant open lab. “The field is getting more polarized,” jessica dai tells me.

Back in the Bay, I attend a friend’s birthday to sip non-alcoholic beers and talk to more AI researchers, then plant myself at a coffeeshop to grind out this post (the table next to me is debating whether 2026 will finally be the “year of agents”). There’s a Partiful notification on my phone: one of the women who cohosted the infamous TITS 2017 skipped NeurIPS this year, but is throwing a holiday party in Pac Heights. In my email, a Luma digest lists the week’s SF events: “AI Agents Meetup: Cursor + Langchain,” “-1 to Microsoft with Kevin Scott,” “Frontier AI Paper Reading Group: Post-NeurIPS 2025.”

Wherever you go, there you are. I guess I didn’t need to leave.

misc links & notes

I am very open to believing that all my impressions are bunk because I’m not a researcher and don’t understand the academic value :)

Here are some fun stats & resources about this year’s NeurIPS papers:

Every accepted paper on a cluster map with an ELI5 (props to Jay Alammar)

Top institutions by accepted paper count, 2015-2025 (Google and Tsinghua/Peking on the rise)

Paper topics in US vs. China vs. Europe vs. Rest of World (Europe likes explainability, China likes computer vision)

Thank you to jessica dai, among others mentioned here, for feedback & conversations that informed this essay.

the luckiest people alive

Even if you’re making a $50k/year grad student salary, that puts you in the 90th percentile of all humans, even adjusted for US cost of living!

That’s why I’m part of GiveDirectly’s December Substack fundraiser. GiveDirectly sends cash transfers to the poorest people in the world—in this case farmers in Bikara, Rwanda—which means your money goes a long way: for $35, you can buy a month of food for one person, or for $200, a semester of university fees.

Substackers have collectively raised $988k so far. I’d love to help make that $1 million. You can donate here:

We’re some of the luckiest people alive.

Party on,

Jasmine

The old acronym NIPS—pronounced as it’s spelled—was officially changed after Long Beach 2017, when a few things happened in quick succession: a friend group hosted TITS, a satirical preconference party with Ethereum tickets, Elon Musk made several crude jokes at an onstage keynote, and a startup sold “my NIPS are NP-hard” t-shirts. That year, Intel also hired Flo Rida to DJ a club night, only to have him yell “Where the ladies at?” to a dead-silent room of men in backpacks. Women in the AI/ML community’s patience with sexual harassment had reached a tipping point long ago, and finally, the name was changed.

Supposedly established after Canada rejected the whole Qwen team’s visa applications last year.

Per an informal survey, only ~70% of NeurIPS 2025 attendees knew what AGI stands for, but 95% know SGD!

I previously wrote that there weren’t OpenAI folks, but apparently I just didn’t run into them, and there were five.

Later in the conference, an analogy for how we’ll think about human value after AGI: “Grandma is not economically valuable but she’s also not a pet.”

Lily’s full karaoke report:

The event was hosted at HIVE in San Diego’s Pan-Asian Convoy District. Among the attendees were several Singaporeans who regularly do karaoke together in SF. That group included our host, swyx.

The invite said the event started at 10 and encouraged everyone to come early. I showed up at 9:45 to find out that the singing would actually start at 10:30. The purpose of this schedule fudging was made clear by the number of people who walked in at 11:40, even though the reservation in theory ended at 11:30 and the venue was supposed to close at midnight (HIVE very kindly allowed us to sing until 12:20).

My karaoke songs in order: “I Will Survive,” “Poker Face,” “Your Love is my Drug.” I would have preferred to sing Russian pop songs or Taiwanese rap, but these were shockingly not in the venue’s song library. Save for a few lines in one KPop Demon Hunters song, the party only sang in English the whole night — even though there were some older Mandarin songs available and the crowd was even more disproportionately Asian than the conference as a whole.

The party was probably about 70:30 male-to-female. I find myself quite endeared by the bold self-expression of male karaoke, and the singing seemed particularly cathartic after a long day of Communicating. The biggest crowd pleasers among the gentlemen in the audience were “We Will Rock You,” “Rap God,” “In the End,” and “I’m on a Boat.”

The star of the evening was Kyle Morris, who wrote a musical about the AI industry with showings in SF. He explained to me that his musical is about “inventions that cannot be controlled by their creators, like children who disobey their parents or founders who disobey their investors. It’s satire — think The Book of Mormon for AI safety.” Kyle absolutely destroyed all of us with the quality of his singing.

I endorse Kyle’s musical, which he co-acted and produced with Scott Fitsimones and Belinda Mo. It’s really good!

"“So how did you estimate one day as the GDP doubling rate?” I ask.

“Just vibes,” his friend replies. “Like, that’s how fast bacteria double."

Of course. Just vibes all the way down.

I personally learn more in the comments section of my Substack than at NeurIPS. My experience has been negative since Zuckerberg showed up in 2013 and started pitching people to sell out to Facebook. I haven’t been since 2017. But the conference is now serving multiple purposes at once, and some of the academic ends aren’t legible unless you’re an eager grad student with the right mindset.

I sent this piece to a colleague in Europe, and he replied with an interesting perspective:

“A few of my postdocs/students were there, and their report had a totally different vibe. They have been only a few times and have only seen this version of the conference. They went to the poster sessions, gained a sense of current scientific trends, and were invigorated by the energy. Probably this wouldn't have been my experience, and yet it might be for a lot of kids from random places around the world, don't you think?”