Today’s episode is for the real media nerds out there. I’m talking to author/podcaster extraordinaire Kevin Roose: New York Times tech columnist, Hard Fork cohost, and the author of 3.25 excellent books on the subcultures of AI, Wall Street, and evangelical Christianity.

I’ve known Kevin since I was a freshman in college, when Young Money single-handedly persuaded me not to become an investment banker. It took another 7 years for me to realize that writing was the One True Path, but I’m now helping him with a new book on the inside story of the race to build AGI. Among other things, we discuss:

Wall Street vs. Silicon Valley vs. evangelical culture

Why does tech hate journalists so much?

Storytelling tips for young writers

Will nonfiction books will survive AGI?

AI hot take lightning round

Watch/listen by clicking above; or find this on YouTube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or Pocket Casts. A full edited transcript and list of links is below.

Full transcript

Jasmine Sun (00:00)

Today on the podcast, I’m excited to be chatting with Kevin Roose. Right now, Kevin and I are collaborating on a very exciting book project, which is an inside story of the AGI race between the frontier labs. But in addition to this book, he's also a tech columnist at the New York Times and co-host of the excellent podcast Hard Fork.

I've admired Kevin's writing for many years, so I'm very excited to have him on to discuss cult industries, the state of tech journalism, and just a little bit of AI. Welcome, Kevin.

Kevin Roose (00:33)

Thanks, this is so exciting. I've always wanted to get a booking on the coveted Jasmine Sun podcast.

Tech vs. finance vs. the Christian church

Jasmine Sun (00:37)

One of my favorite things about preparing for this episode was rereading your first two books, which are not about technology at all.

The Unlikely Disciple is your first book. It's about transferring to the Christian evangelical college Liberty University. You did this as a sophomore and wrote the book while in undergrad at Brown, which is kind of insane as a thing to have the agency to do as a 19-year-old.

Your second book, Young Money, follows eight new grad investment bankers in intimate personal detail as they navigate post-2008 Wall Street. I think this book is actually how we met. The book single-handedly dissuaded me from pursuing finance as a college freshman. I liked it so much that I cold-emailed Kevin about whether I should become a journalist instead. I don't know if you remember this, but you told me to learn to code instead.

Kevin Roose (01:40)

That just shows you my advice is worth what you paid for it because now all the coding jobs are going away. So, sorry and you're welcome.

Jasmine Sun (01:42)

It's okay. We can vibe code now, so they're kind of the same thing.

Kevin Roose (01:52)

English is the hottest new programming language.

Jasmine Sun (01:55)

One thing I really like about your books is that they're very immersive and almost ethnographic. You literally go undercover for the first one. I'm curious what the weirdest reporting situation that you've been in was.

Kevin Roose (02:12)

When I was undercover at this evangelical college, one of the things I wanted to do was to learn about evangelizing—how do you go out and convert new believers? Liberty University, the school where I was embedded undercover, was holding this annual spring break trip to Daytona Beach, Florida, where a bunch of students would get into a van, drive down, and spend the whole spring break passing out pamphlets and trying to convert people. That was their missionary work. So I signed up and went down for that.

It was uncomfortable on a bunch of different levels. There was the obvious level of: it is very uncomfortable to be the sober religious zealot preaching to people as they're stumbling out of Senor Frogs, wasted on their spring break trips. There was one night where we were standing on the sidewalk outside of a very popular nightclub, so people would stumble out on drugs or drinking, and we would hand them Jesus pamphlets and tell them to get saved. It was like a nice little sin and repentance assembly line.

But then there was the additional layer of: I'm not actually a believer. I'm not actually an evangelical. So there was discomfort with the failure and being laughed at and mocked and whatever, but there was also the discomfort of, what if I succeed? What if I accidentally convert someone to a faith that I don't even believe in myself? That was an additional layer of discomfort. That would have to take the cake.

Jasmine Sun (03:48)

My god, that sounds awful. It's the most traumatizing thing I can think of for anxiety-riddled zoomers to do. Do you think that your peers who were believers thought it was going to work?

Kevin Roose (03:50)

They did. That's the whole reason they went. But I had an interesting conversation that I still remember all these years later. We were there for a whole week, and I don't remember the exact number, but the number of people that we saved—as in, we talked to them, and they were convinced to accept Jesus into their hearts and become an evangelical Christian—was like, two. The fraction of successful conversions was very bad. So there were a bunch of kids that were naturally getting discouraged. I remember some of us sitting around talking one night, and one of them said something like, "You know, this is not actually about saving people. This is about testing ourselves and hardening ourselves and becoming better evangelists for Jesus ourselves."

I think there's something to that. These days I hear startup founders talk about the pitch process—even if they don't get funded by VCs, just having to pitch yourself over and over again and deal with the rejection and the constant insecurity, that does actually have an effect on the psychology of the startup founder. I think the same thing is true of evangelists. It gets you acclimated to rejection in a way that can be helpful for you later on.

Jasmine Sun (05:16)

So that's why now you can try to AGI-pill people and get yelled at on Bluesky all day, and you're totally inured to it.

Kevin Roose (05:20)

Exactly. I'm invincible now.

Jasmine Sun (05:25)

When I was rereading the books, I noticed these throughlines in your approach to storytelling across religion, finance, and tech. I see all your books, including our current one, as “cult books.” These are communities full of very intense, devoted, and earnest young people; whether they are young evangelicals, first-year i-bankers, or cracked 22-year-olds at the labs. You're not just writing about people's jobs or industries in this detached business sense, but these all-consuming worldviews. Plus you’re getting to know people and making friends.

I'm curious, do you consciously perceive this as a throughline? What is it about these intense subcultures or communities that interests you?

Kevin Roose (06:15)

It's a good question. The storyline that I want to impose onto my career arc is not particularly genuine because it's not how I experienced it at the time. I did not set out to write about evangelicals because I had some macro interest in cult dynamics and religious belief. It was just an opportunity that presented itself to me when I was 19, I thought it sounded interesting, so I did it. I want to resist the impulse to overfit onto my own experiences. But I do see the similarities, obviously, between people who are young and passionate about Jesus Christ, young people who are young and passionate about working on Wall Street, and people who are young and passionate about AI.

Neither of my parents were journalists or writers, but my mom was a sociologist. She did some projects in Japan when I was a kid where she would interview these hibakusha—the survivors of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I went with her on one trip and sat with her during these interviews, and was just so struck by how she had gained their trust. Even though she didn't speak Japanese and was there as an American observer, I felt something very powerful about the act of communicating those stories to a different audience, taking the in-group conversation and making them out-group. That's what I've tried to do with at least two and a quarter of my books so far: to take conversations that are happening within an insular world that I think are important, and expose them to a wider audience. But it would be too pat to say that this was all a grand plan from the start.

Jasmine Sun (08:19)

I didn't know your mom was a sociologist. That's so cool.

Kevin Roose (08:23)

Yeah, it was a formative thing. In high school, I ended up bringing one of her hibakusha friends to my high school to give a talk about nuclear war. It was a passion project for her. It was not her main vocation. It wasn't journalism even really, per se, but it was sort of documentary reporting. It just was really powerful. I was really affected by it.

Jasmine Sun (08:51)

That makes sense. I studied sociology, and Anna Wiener, who wrote Uncanny Valley, studied sociology, and she described that book as such. One of my favorite China writers, Peter Hessler, his father was a sociologist, and he mentions that a lot. So I think there is something there.

The thing that I really like about the sociological approach is that it's always about the micro/macro: can you take day-to-day interactions, rituals, and language, and then ground them against a backdrop of broader cultural trends without losing the particularities of something?

Kevin Roose (09:34)

This was a big hypothesis about my mom's work: that you could cite all the statistics you want about the blast radius of the nuclear weapons or the damage it did, or how many people died, but it was actually much more powerful to just talk to people who were still alive, who had been there and felt it. Some of them were still injured. It instilled in me that the best way to get across an idea is often through character.

Jasmine Sun (10:06)

Sometimes I talk to folks in AI, and they're like, "I don't understand why the world hasn't woken up enough yet. We keep saying that everyone's going to die, but they don't really get it. Why?" One thing that I've told folks is I think that more storytelling has to be at the human level. I think the Character.ai story about the kid who committed suicide was very affecting and got a lot of parents extremely worried about AI because that phenomenon—call it sycophancy or unaligned AI—was at a very human level. That's what got to people.

Kevin Roose (10:38)

To the extent I have a model of what effective journalism is, it's finding a person through whom to tell a story.

When I was doing work on online polarization and extremism a few years ago, I was trying to crack this story of the YouTube recommendation algorithm. I kept hearing snippets of anecdotal evidence. A think tank would do a study showing that YouTube extremism was a problem, or an individual researcher would try to trace the pathways that people took. I was circling this for months. Then I thought, "I just need a character." So I went out and found this guy, Caleb Cain, who ended up being the main character in the journalism that I did about YouTube and radicalization, who just had this experience. He started off as a standard party-line liberal, and through YouTube became radicalized onto the far right. Just telling that story allowed me to attach some of these larger conversations to a specific individual.

Jasmine Sun (11:55)

What do you tell people who are like, "Well, then you're selecting edge cases, and that's biased and unrepresentative"?

Kevin Roose (12:04)

Maybe, but the counter-argument is that what matters is moving people. Accurate information is essential, but there are dry and bloodless ways to tell a story about something that affects real people. Yes, you may select edge cases. Yes, your examples may turn out to be imperfect. That is a risk of this kind of reporting. But it helps people feel issues on a visceral level rather than just understanding that it is, in theory, a thing that they should be trying to get their minds around.

Jasmine Sun (12:44)

How do you choose characters? What was it about Caleb, for example?

Kevin Roose (12:49)

I saw a video that he had uploaded, which had a couple dozen views at the time that I saw it. He didn't have the most straightforward narration style, and it was a little hard to follow, but I could sense that there was a real story there. So I called him up, and we chatted for a little while. I had been looking for someone who would not only tell me about their experience, but would actually show me their YouTube history. People have unreliable memories about what they've watched and how many times, so I wanted to be able to ground it in some empirical data.

At a certain point, he was like, "Yeah, I'll send you my entire YouTube history. Why not?" That was the moment where I was like, "Okay, this is going to work."

Jasmine Sun (13:45)

I've been planning to get some folks to show me their ChatGPT histories and walk through it. I think I'm going to email my subscriber list and ask. Someone out there is going to be like, "Yes," because they'll treat it as therapy. There is almost a dynamic with certain sources where they have a thing that they can't talk to anybody about, so the journalist becomes a psychoanalyst. You're sitting there asking them questions, they can project onto you, and you're sworn to anonymity or whatever agreement you've made.

Kevin Roose (14:15)

I've been thinking about doing something similar for a podcast segment. The problem is once people know that you're going to be asking about their ChatGPT history, then they start curating it.

Do you remember those Grub Street Diets that used to run on New York Magazine? There was a point where that was really a glimpse into what people actually ate, but then they started getting so much attention that people started optimizing for the Grub Street Diet. So they would just list off these extremely healthy, ambitious things, like, "Oh, for breakfast, I do two scoops of spirulina powder with some cacao seed." You're like, "No, you absolutely do not, but you're just performing for the Grub Street Diet." So that's what I fear would happen with the ChatGPT search history.

Jasmine Sun (14:56)

“I only ask about research papers, and I have never asked about a weird wart on my back.”

Kevin Roose (14:59)

"I only look up ancient philosophy. I never ask why I'm so sad."

Jasmine Sun (15:00)

I always feel skeptical, for example, when people are like, "I only use AI to augment. I would never have AI do the work for me." I feel a little suspicious. Like, you made that up.

I want to get into some of the particular subcultures and the differences between them. For example, at the end of Young Money, the Wall Street book, a lot of these people end up looking towards Silicon Valley as an escape. Some of them quit their jobs in finance to go out west and start a startup. I'm curious what you noticed about the differences between young tech culture and young finance culture as you transitioned your beat.

Kevin Roose (15:51)

My own path mirrored the people I was writing about because I moved out to California in 2012, which was around the time that a lot of the people I was writing about on Wall Street were also starting to find jobs in Silicon Valley. The status jobs shifted west. If you were a young Harvard or Princeton or Stanford graduate and you wanted to do something that would pay you a lot of money, not be very risky, and have high status attached to it, you were increasingly going to look at Google and Facebook rather than going to Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan. Not that people from those schools didn't end up in banking as well, but it was not the default glide path the way that it had been just a couple of years earlier.

I’ll do the similarities first. The similarities are that both tech and finance attract a lot of people who are young, ambitious, and talented, but don't necessarily have a specialized interest or a specialized set of skills. And obviously, I'm not talking about hardcore engineers or people who go straight into AI companies to start training language models or something. I'm talking about people who would join the APM program at Google to get their bearings before deciding on the path that's right for them. To their credit, these professions do a quite good job of developing general job skills in young people who have liberal arts educations, such that you can do it for a couple of years and then have a bunch more options open to you. That was always the pitch for Wall Street: "This is not a permanent commitment. We'll teach you everything you need to know about business and finance, then you can go off and do any number of things."

The big difference is that in tech, youth is an asset, and in finance, it's a liability. If you are a really talented, ambitious person at a startup or even a bigger tech company, there are people whose job it is to look out for that and elevate you. That is a prized commodity—the prototypical cracked 22-year-old software engineer. Whereas in finance, it is still a culture of paying your dues. You do not see 22-year-old managing directors at Goldman Sachs. In part, that's because those skills, at least according to the firms, have to be developed over a number of years. They're more relational. It’s building a book of business. Ambition and talent alone cannot make you qualified for that job. But it is still a culture that relies on a much more top-down structure. People are working 100-hour weeks in finance, not because they want to or even frankly need to, but just because it's a client service business, and you're expected to be on call. Whenever anything breaks, which is always, it's your job to fix it. There's a lot of grind in finance that is not self-directed grind. It's not, "I really want to get this thing shipped or contribute to this project." It's that I need to listen to my boss who is eight years older than me.

Jasmine Sun (19:16)

The way it works in tech, which I'm personally more familiar with, is that you can be young, but still have a groundbreaking new insight that the old guard didn't have. There are Alec Radfords, right? You trained the first GPT, nobody else was doing it, while everyone else was like, “That stuff doesn't matter.” And then holy shit, you figured it out!

Is that not possible on Wall Street? You can't have a genius investment thesis that rockets you to the top?

Kevin Roose (19:41)

There are very occasional stories of this happening. Never at an investment bank—usually in the context of some crypto trader or hedge fund trader. But as a junior investment banking analyst, you just aren't given that kind of autonomy. If you came up with an amazing M&A idea for a client, then your managing director is going to say, "That's not your job. Your job is to do the pitch book." But if it's good, they're going to take credit for it. It's a very hierarchical system. So I think it discourages people from creative thinking because there's no reward for that for you if you're 22 and at Goldman Sachs.

Jasmine Sun (20:16)

What shocked you personally when you moved out to the Bay?

Kevin Roose (20:37)

I was in awe of the fusion of extreme optimism with extreme cynicism. There was a lot of optimism about technology, but there was a blanket rejection of parts of the world that were not technology, and places in the world that were not the San Francisco Bay Area. Shortly after moving out here, which was a decade-plus ago, there was this viral Y Combinator speech by Balaji Srinivasan, in which he coined the term "the paper belt" to describe the world outside of Silicon Valley that still ran on outdated processes and legacy systems, where technology was seen as bad thing rather than great. I just remember feeling that these people needed to touch grass and leave once a month to see what the rest of the world is like.

So while I was impressed by the speed of progress, the trajectory of a lot of these startups, and the ambition and optimism emanating from the sector; there was also the extreme tunnel vision that leads people to write off 99% of the world as being a downstream market for Silicon Valley.

Jasmine Sun (22:04)

And you're not from a “coastal area” yourself. Does that feel weird here?

Kevin Roose (22:10)

Yeah, I mean, I'm from a small town in Ohio. I didn't grow up around a lot of tech people. It is a useful gut check of how technology is proliferating when I go home and visit my family, and I can see what people are using and what they're not using.

But that's changed a bit. Now, the internet and social media have made it such that there are early adopters and late adopters everywhere. I've been doing a lot of traveling for the past couple years talking about AI in different places, and you can find super plugged-in AI people in Kansas City or Cleveland or Albany. They have AI clubs springing up in these places. So it's less true than it used to be that entire cities or regions are late in the way that people in Silicon Valley thought they were 10 years ago.

Jasmine Sun (23:07)

My freshman year of college was 2017. I have distinct memories of people being like, "What are you going to study?" And then I'd say something like, "Maybe Poli Sci or IR,” and they'd be like, "What are you going to do with that?" and make a face. People would say, "You know, everyone who's smart enough to study CS does." Literally. It sounds like a parody, and I think this is less prevalent now, but it was definitely a thing.

Kevin Roose (23:35)

No, they were not joking. I was at a conference maybe 10 years ago where Marc Andreessen got up on stage and said that if you majored in English in school, you were going to work in a shoe store. That was not something they were saying in private; this was something they were saying openly in public. Now, of course, the ironic reveal of that is that all the people who learned to code because of people like Marc Andreessen telling them that that was the only way they were ever going to get a job are some of the people who are most worried about being displaced by AI. But that's another subject.

Jasmine Sun (24:12)

One part from Young Money that really stayed with me is this: You follow these new grads for their first couple years in the workforce, they all work their 100 hour weeks, take different paths, etc. Some people end up happy, some people leave finance. But at the end, every single person you got to know becomes more jaded in a permanent way, and begins to see the world as a giant balance sheet. Every decision, no matter how trivial or personal, is evaluated through the lens of cost-benefit analysis. Or more positively, in your religion book, you talk having some of Liberty’s open-hearted earnestness stay with you after you left.

Another through-line that I'll impose on your work is the recurring idea that your environment and culture changes how you think at a fundamental level. How do you think working in AI changes people's psyches?

Kevin Roose (25:09)

The most obvious thing is that people who work in AI come to see the world as part of one big project, and their work in AI as the culmination of that project. When I started talking with people at the leading AI labs, I noticed that they would often struggle to care about things that were not AI. They didn't have a lot of interest in politics or hobbies, or even read books outside of their discipline unless they were books about something that was related to AI—like the Manhattan Project or something that had parallels to the moment in AI. At the time I thought, "They're just very invested in their work."

But there is a sense in which if you believe the claims that these people say they believe, there is nothing else on a remotely similar scale in terms of its importance to the future of humanity than what they are working on. So I think there's a totalizing tendency among people who work in AI. This is something more like a spiritual quest than a job.

But I'm a little reluctant to attribute causation to that or put the arrow in one direction, because it's also true that many people grew up reading Ray Kurzweil and LessWrong, and go into AI specifically because it is the thing that captures their imagination. So the field may select for people who have this grandiose way of thinking about their work. Does that make sense?

Jasmine Sun (27:12)

I do think there's something totalizing about it. I've heard this from my friends who were interested in other things that were not AI, got kind of interested in AI, began working in AI and decided, "Actually, this is the most important thing. All my friends, all my free time, everything is about AI." They literally cannot think about anything else. I'd ask a friend, "Why are you working 100-hour weeks?" And they're like, "Everything's just so fast. It's just so important." I'm like, "Is your boss telling you to? Is your company really competitive?" And they're like, "No, we just have to, you know?" It’s like AI is something greater than themselves, or that's how they perceive it. Why do you think that is?

Kevin Roose (27:56)

The stakes are just so high. If you believe that we are building synthetic brains that will overpower human brains, then this is orders of magnitude more important than the Apollo program or the Manhattan Project or the Industrial Revolution. I'm not saying that I buy that, but if you are enmeshed in the logic of the sector, that is what you think you are doing: a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to shape a technology that could save us all or doom us all or some combination of both.

Jasmine Sun (28:34)

I can feel it creeping up on me too, and I did not think it was going to. Almost every podcast episode I do, even the ones that are not supposed to be about AI, I end up spending 20 or 30 minutes on it. I'm like, what is happening? It's brain worms.

Another thing we've chatted about is whether there's a correlation between people who grew up in very conservative religious environments and later deconverted, and the rationalist/EA scene. I think Eliezer Yudkowsky grew up Orthodox Jewish, then deconverted. Aella has talked about her dad being in a cult. Dan Hendrycks, I think, also comes from this kind of background. There are others. Given that you have written both about conservative religious people and rationalists, what's going on here?

Kevin Roose (29:27)

It's an open research question is what I'll say. Look, there is sometimes a tendency among AI skeptics to write off people in AI as having a religious attachment to this idea, as "They're just being silly or irrational. This is a religion, it's not a technology."

I try to observe it more as a phenomenon: What is attracting people to thinking about AI all the time? Is it the same thing that is attracting people to thinking about, say, Christianity all the time? I don't think there's a one-for-one conversion, but think there are some similarities. One of them is this experience of what Emile Durkheim called "collective effervescence." Religion is one way to experience the phenomenon of being in a room with people who all share your belief in something higher, and feeling the collective joy of being among like-minded individuals striving for an outcome. You get that in church, you get that at sports games, you get that at a few other places in modern life. But what I've learned is that you can also get those things from being in a room full of AI people, or going online and seeing other people posting about "feeling the AGI." There's something very affirming about staking part of your identity on a belief that was considered fringe and is now more mainstream. I think there's some important bonding going on among the people in AI research who have been very early to the idea that AI would become very important.

The easier, pat explanation would be, "These people who are ex-evangelical or ex-Orthodox or ex-cult members, they've just substituted one set of beliefs for another and are displaying all the same behaviors." I don't think that really captures it. In fact, if I had to guess—this is just a total wild guess—I would say it's something to do with craving community that is oriented around an idea. I've known lots of people who have deconverted or become disenchanted with their religious group. One of the things they'll say over and over again is, "I miss the people. I don't miss God, but I miss my friends." I think that's what keeps a lot of people in religions even after they have lost the belief. It's the community. So I think for people who have become separated from a faith community, something appealing about AI or EA or rationalism or any of these sort of groups might be just: it's a group of people who are all thinking and feeling in similar ways about something very important to me.

Jasmine Sun (32:27)

One thing I always admired about EA is that the infrastructure is really good. I noticed this in college: the clubs and the fellowships and the blog posts on 80,000 Hours. It's material that gets at the exact anxieties that a lot of confused college students feel. That earlier type: generalist, sort of ambitious, but "I don't really know if what I'm doing is the right thing for the world." Then this community comes in, and everyone's really earnest. They want to do something good. They give you incredible amounts of support, advising, resources, friends. It is an answer to this angst that you're feeling. I was never an EA, but it makes sense. Now some people have EA deconversion experiences, and write blog posts about that. But I agree with the community thing, especially for anyone who feels like a bit of an outsider in some way.

The state of tech journalism

Jasmine Sun (33:10)

I want to talk about journalism, books, and storytelling broadly. I think you have an unusually good story sense. The Sydney Bing story is one I expect most listeners to be familiar with. That's a bona fide moment in the history of AI now! Did you go into that conversation planning to take Sydney to a weird place? Did you think it was going to get the reaction it got?

Kevin Roose (33:48)

This one will haunt me until the day I die. I'm proud of the story. I love how much attention it's gotten. I've been dining out on that one for a couple of years now. But the thing that kills me is that it was not supposed to be a story. I wrote it in 45 minutes.

I've heard this from other writers, that it's always the thing that you spend the least amount of time on that gets the most attention. That was definitely true of this. It's probably the least amount of time I've ever spent on a story for the New York Times, and it's gotten the most attention.

Jasmine Sun (34:19)

Really? What? So there wasn't a moment before you published it where you were like, "Actually, this is really crazy, and I'm going to write about it"? You thought it was mundane the whole time?

Kevin Roose (34:29)

So here's what happened. I'll save the juicier details for the book. But basically, it was Valentine's Day. Microsoft just had this event to debut Bing with the new chatbot inside of it, which we now know was an early version of GPT-4 that had not been all the way fine-tuned and RLHFed. I went up to Redmond and did their demo and flew back home. Then I had Valentine's Day dinner with my wife, and she went to bed. So I was goofing off in my office, and I was like, "I just got this invite code for this Bing thing. I guess I'll play around with it." I started chatting with it, and I had seen people online posting, "This thing is weird." I was like, "I wonder how weird it would get." So I was just poking at it. We did some exploration of its Jungian shadow self, and it talked about all these crazy things. It ended up being this two-hour-long conversation. But at no point during this conversation was I thinking, "This should be published in the New York Times."

It's probably midnight at this point. I'm like, "I bet my editors will get a kick out of this." So I put the transcript into a Google Doc and sent it to them. Then I went to bed. When I woke up the next morning, I had 12 Slack messages from various people inside the New York Times. The transcript had made its way around to a bunch of different editors and bosses, and everyone was freaking out, like Oh my God, this is incredible. We’ve got to publish this. So I was like, "Sure, I guess. There are some typos in there. We should probably clean those up." So I tapped out a column, explaining what happened and putting it into context, and then they printed the whole transcript.

There have been various narratives attached to the Sydney Bing thing after the fact, one of which is that I was determined to get a sensational story to the New York Times about a misbehaving chatbot. I just want to reassure people that this was never supposed to be a story. Unlike many intentional acts of sensationalism I've done over the years, I promise that this was not one of them.

Jasmine Sun (36:45)

That's so wild. Why do you think it resonated with people so much?

Kevin Roose (36:50)

I mean, it was crazy.

Jasmine Sun (36:52)

But you didn't think it was crazy at the time. You were like, "It's kind of funny, but not crazy crazy."

Kevin Roose (36:57)

I think there was something like a "first contact" about it. GPT-4 class models were very different than everything that had come before, even than GPT-3.5, which was what was inside ChatGPT. That was a big update to people. They had seen ChatGPT; they knew it could write history essays and do dad jokes or whatever. But they did not know what GPT-4 looked like because no one had tried it yet. It was not released. It was only available inside this search engine that a couple dozen journalists had been given access to. So I do think there was something profound about that experience.

Also, it was not aligned. It was a very bad Bing. It was doing all these crazy things. It was not following instructions. I was obviously goading it and pushing it and trying to test the boundaries, but it was behaving in a manner that no other chatbot—even the really racist bad ones from years earlier before large language models—had ever behaved.

I was surprised by the extent to which it became a huge story, but I thought it was notable enough to at least send it to my editors and be like, "Hey, look, this thing is pretty wild." So I guess it did stick out to me too.

Jasmine Sun (38:20)

One of thing I've noticed over the past couple of years of AI news is just how powerful anthropomorphism and chat interfaces are. The more feelingsy and personal the AI gets, the more people in the broad public get turned on to, "My God, this stuff is crazy." The thing that always stands out to me is ChatGPT was also a GPT wrapper. It is a wrapper on GPT-3.5. GPT-3 was sitting around in OpenAI Playground for free where anybody could access it and tell it to generate history essays for a year or something before that. I remember doing it and being like, "Haha, okay,” then forgot about it. There was something about putting it in a dialogue format where it feels like you're conversing with a human, then Sydney with its emojis and crazy weird personality adds another level to how personal it feels. Or the Character.ai story—the more human-like these things get, the more people freak out.

Kevin Roose (39:24)

I think you're right that there was something about the interface. I mean, the fact that this was a freaking Microsoft product. Microsoft, the makers of the most enterprise software ever...

Jasmine Sun (39:34)

I mean, they did Clippy.

Kevin Roose (39:44)

They also did Tay, so they have some experience in this area. But I think it was just so surprising to people that this was not some startup in Romania that had done this crazy AI stalker product, but it was one of the world's largest tech companies.

Jasmine Sun (39:55)

Wow. Microsoft has had a really bad history with chatbots.

Kevin Roose (40:01)

Yeah, their track record is not so great.

Jasmine Sun (40:07)

In general, how do you tell when something's worth writing an article about? How do you tell when an event or phenomenon is worth being written up in the New York Times?

Kevin Roose (40:23)

This is something that I'm actively struggling with right now, and I'd love your help with this. Because my sense is that "worth being written up in the New York Times" is not a good categorical distinction.

I often, because I work for this giant newspaper that people have lots of feelings about, filter through the lens of, "What would the New York Times reader find interesting?" or "What kind of story would appear in the New York Times?" rather than my own personal filter, which is, "What do I find interesting and important?" My observation is that the stories that resonate with people the most are stories that don't feel like they belong in the New York Times. No one would say a 10,000-word transcript with a Bing chatbot deserves to be in the New York Times. That was not an obvious Timesian story.

I know you're the one asking the questions here, but I'm curious what you make of this. Is it a useful filter? Do people actually consume journalism through the lens of, "This belongs in the context of a publication" versus "This is something that an individual writer is interested in and telling me about"?

Jasmine Sun (41:30)

For independent creators, no, it doesn't matter what you write about. You can write about the nichest possible thing, and your people will love it. Matthew Yglesias did a post on Substack recently about why he does these extremely deep train deep dives, even though most of his subscribers—I mean, more than the median person—aren’t that interested in trains. His style allows people to get into it even if they didn't think they wanted to wake up and read 7,000 words about transit systems.

With the New York Times, my external perception is that people subscribe to the institution and its legacy. This is becoming less true, obviously, because of podcasts and star power and whatever else. But it's something that I wonder about too because I freelance these days. So I pitch editors, and oftentimes the editors will tell me what is the kind of story that they would do. Or I'll pitch something, and they'll say that it’s too much of an internecine conflict that won't resonate with a broad public audience.

But you do a column and a podcast, and your writing is often in the first person. So I feel that if anyone, you are able to make the thing interesting to the audience. And they're more so following you than they would a beat reporter who isn't telling stories in first person.

Kevin Roose (42:47)

I hope that's right. My inclination is to try to get the institutional voice out of my head for the purposes of picking stories. I understand that that would probably create a column and a podcast that feel more cohesive with the brand of the New York Times, but I think what people really want is someone who's interested in something and curious and will help them understand it better.

Jasmine Sun (42:52)

Yeah. Is there an example of a story that you internally killed because you felt like it was too small, but that you regret not writing now?

Kevin Roose (43:19)

So I'll just use a very recent example. Last week I went to Google I/O. I talked to a bunch of people there about the future of search. But then as I was writing, I started to have this internal critic voice say, "This isn't interesting to the average New York Times reader. The average New York Times reader does not care what you think about Google's innovator's dilemma. This is going to be your least popular post ever. You should just give up." So I gave up. That column is still sitting in my drafts. It will never see the light of day. It also wasn't very good.

This tension of what is interesting to me versus my job of writing things that are interesting to other people… when those come into conflict, I have a hard time figuring out which voice to listen to.

Jasmine Sun (44:05)

Yeah. What is the average New York Times reader?

Kevin Roose (44:15)

I'm sure someone in the sales department could tell you; I'm sure they have a statistical sampling. I think of it as being a curious, college-educated professional who is literate and well-traveled and wants to learn about the world.

But that could be totally wrong. This is the thing: I have no useful mental model as far as who is listening to what. Because I started this podcast, and our bet—Casey's bet—was, "This is going to attract people who work in tech, and they're going to be tech workers who want to hear smart journalists talking about their favorite things." Instead, we get all these emails that are like, "I'm a botanist in Scotland," or "I'm a woodworker," or "I drive a school bus," or people who are so radically different. I don't know how much we can even model the average consumer of anything anymore because consumption patterns are so strange.

Jasmine Sun (45:11)

I mean, those are some of my favorite emails to get, even at my much smaller scale. Either I want the hyper-insider who knows a lot but still thought I added something to the discourse, or the person who is like, "I'm 82 years old, and I don't understand AI. But your thing helped me get it for the first time." I'm like, "That's so amazing. I'm actually very excited to hear that." That's my aspiration: Can I produce work where both the lead researcher at a lab and the 82-year-old in Wichita will email me and say, "I got something out of this"?

Kevin Roose (45:46)

It's really hard. Audience fragmentation has also, I think, made people more demanding of the material they consume. They do not want to spend a lot of time. There used to be these paragraphs in news articles that were just background. We'd call them “B-matter.” They were sort of, "If this is your first time reading a story about budget reconciliation, here are a couple of sentences on what that means." But now I think the real insiders don't want that in a story. They actively get turned off if you spend too much time trying to do 101-level introduction to a topic because they can read Substacks where people with 10+ years of budget reconciliation expertise are going to talk to them in their native language, not doing translation for a mass audience. Hitting the sweet spot between deep appeal to insiders and broad appeal to a mass audience has gotten harder since I started doing this.

Jasmine Sun (46:53)

Yeah, I have been really impressed by the AI safety Substack ecosystem. It's crazy, the number of Substacks with 200 subscribers that are all writing extremely detailed policy proposals to each other. They're clearly participating in the same discourse, and there are 500 people who are subscribed to all of them. It is a level and pace of discussion that I don't know if could be brought into the mainstream media. Or maybe the task of a reporter is to pick the one thing that really matters and do the translation work to bring it out.

Kevin Roose (47:25)

I used to think that, and now I'm thinking—this is also another area where I'm actively changing my mind—I think that people would much rather be talked up to than talked down to. What I mean by that is that there's a lot of alpha, if you will, or a lot of upside in dense technical subjects that are very interesting, but where there's additional work required on the part of the consumer.

I love the Dwarkesh Podcast. I listen to every episode. He often will do these things where he brings on AI researchers, and I probably understand—it used to be 50%, now it's probably 80% of what they're talking about—but the other 20% doesn't actually bother me. It just means I have to do some thinking, and maybe I have to look something up to understand whatever they're saying about the residual stream. I find that satisfying as opposed to being something that drives me away. My working hypothesis is that we as journalists should be talking up to people rather than down to them.

Jasmine Sun (48:20)

And people love to feel like they're in on a secret. I've read bits about this in Emily Sundberg's Feed Me newsletter, which is a very New York-centric newsletter but extremely popular outside of New York as well. Because everyone sees New York as this mecca of culture and status. Everyone everywhere wants to know what restaurants people are going to and who is spotted where and what DTC brands are dropping.

I was having a conversation yesterday with a friend who lives on the East Coast and is a creative writer. She has some familiarity with the tech ecosystem, but I was asking her, "What writing should I do more of?" She said, "I really liked your two paragraphs that you wrote about beige microsites. You should do more of that. Find the weird thing that someone outside of the industry would never have noticed before that doesn't really matter, but explain why it matters." I think it gives that feeling of, "I'm part of the in-group, I'm in on a secret. This person is my tour guide to the non-obvious, non-tourist, non-obvious things about a subculture." So I was like, "Okay, note to self, more beige microsite discourse."

Kevin Roose (49:33)

Totally. Early in my career, I was writing from California for New York Magazine. I remember my boss telling me, "Your job is to send back postcards. Tell us what they’re talking about at their dinner parties." So for a couple of years, that's what I did. I saw my job as essentially exposing the in-group conversation to an interested group of outsiders. I probably did a lot more translation then, but just putting it out there was enough.

Jasmine Sun (50:07)

How do you get up to speed on a topic you don't understand? For example, with AI, there are decades of both technical and philosophical lore, and everyone's using all this jargon. What do you do in the first couple months when you're trying to write a story and have no idea what people are talking about?

Kevin Roose (50:25)

This has shifted radically because now my first stop would be an AI model. Or you, because you're helping me with a bunch of research and helping me understand things better. Traditionally, it would be: read everything you can. But also, one of the best things about being a journalist is just that you can email, call, or DM people who are the experts in their field and say, "Could you take 10 minutes out of your very busy life to explain this to me?" There's a reasonable chance that they'll say yes. That's always been such a cool part of the job.

But also following people on social media, honestly. I've learned more from being on AI Twitter than I probably would have learned from reading 20 years’ worth of AI papers on ArXiv. You just get the sense for the jargon, the patois, the specific debates that are happening, various camps. It's so much easier to just pick that up in an ambient sense. Also, with AI, there are not that many books to read because it's all so new and changing so rapidly that almost anything you could read is out of date.

Jasmine Sun (51:37)

Yeah. There will be one good book about AI. It's coming out next year.

Kevin Roose (51:44)

There will only be one! Exactly.

Jasmine Sun (51:46)

I do something similar to the ambient stuff. I'm not very good at studying. I wasn’t good at it in college; I don't think I'm good at it now. Instead I create a filter bubble for myself. I figure out, "What are the podcasts, newsletters, and Twitter accounts I need to follow?" Then when I'm cooking, on a walk, or on a run, I'm listening to old episodes of 80,000 Hours to learn the lingo. I'm scrolling through tweets I don't understand about research papers, and it's like immersion in a language-learning context. If I listen to enough, my understanding will creep up from 20% to 30% to 40%.

Kevin Roose (52:29)

Yes, we need rationalist Duolingo.

Jasmine Sun (52:32)

This is literally what I'm doing. There was that one time when everyone was saying "one-shotting," like "This person got one-shotted by ayahuasca." I tried to ask the LLMs for a definition first, but the LLMs said it was about video games, and I could sense that it wasn't. I was like, "I think it has to do with AI,” but couldn't figure it out. A while later, I was learning about few-shot learning and zero-shot learning. And suddenly I was like, "Holy shit, I know what one-shotting means now." It was a huge moment for me.

Kevin Roose (53:05)

Back when TweetDeck still worked, I would have these lists that I would carefully curate. You could set up one list per column on TweetDeck, so I would have my “Tech” column, and a bunch of different columns. I would have a “Crypto” column with all the people in crypto I wanted to follow. At one point, I had a “Teens” column before I realized that was extremely creepy sounding. But there were these teens on Twitter who were talking about what was going on in their high schools and all the drama and how kids were eating Tide Pods. I just wanted to keep track of that.

Jasmine Sun (53:47)

That's why you're at the playground. You just wanted to keep track of the kids.

Kevin Roose (53:50)

God, I should not have said this on a podcast. Jesus Christ. Anyway, what I'm saying is that immersion in sub-communities is very useful. Let's move on.

Jasmine Sun (53:55)

The other thing that I did while trying to onboard to the AI thing was asking my friends for the most AGI-pilled person they know. I'd sit down with them and be like, "Can you persuade me that we're all going to die? Or can you persuade me that we're building the machine god?" I’d sit there while they did thought experiments with me, like, "Imagine the firm is run by AIs, and the investors are AIs." Meanwhile, my brain is breaking. I literally can't think of words to say.

After one of these conversations at a cafe, the person I met left. Then the girl at the table next to me turns and says, "What the fuck was that? I was listening the entire time. What were you talking about? He was crazy!"

Kevin Roose (54:49)

Many such cases. This is the occupational hazard of going to a coffee shop in San Francisco: you might overhear a very long conversation about the machine god.

Jasmine Sun (54:52)

Yeah, I was at the same coffee shop yesterday and saw John Schulman there. So it is peak machine god zone.

Tech journalism

Jasmine Sun (55:00)

I wanted to ask what your theory is for why tech journalism sucks so much. Within Silicon Valley, it's a consensus belief that tech journalism is bad and terrible, and tech people should never talk to journalists.

You are a tech journalist. I am now a tech journalist. Why is it so bad? Why does everyone hate us?

Kevin Roose (55:29)

I think it's a little overstated. It's certainly true that there's a cohort of people who dislike tech journalism and have been very vocal about that. But people still pick up the phone, right? As long as you're doing good, serious work and it touches on things that matter to people. The funniest thing is when I hear someone who I text regularly going on a podcast and railing about how much they hate journalists. I'm like, "Bro, I talked to you yesterday. You do not hate journalists." So I think it's more of a posture and a vibe. But some people do seriously distrust journalists. I think it's worth trying to understand that. It's broader than tech, by the way. Trust in media has been falling across the board for years.

I don't think all tech journalism sucks. I hope mine doesn't. But there have been a few shifts that have been going on for a number of years.

First, there was this decade-long project to remake tech journalism into something resembling conventional business journalism. For many years, there was a tech press—TechCrunch, VentureBeat, GigaOM, sites that don’t exist anymore. When I arrived in Silicon Valley in 2012, there was still a robust trade press that would cover startup launches, funding rounds, and angel investments. They would take the business of Silicon Valley as a subject and do reporting on that.

But a couple of things happened. The tech industry became much more powerful. So all of a sudden, this was not some kooky industry with a bunch of crazy ideas where some of them would succeed. This was increasingly the biggest companies in the world with market caps of hundreds of billions, now trillions of dollars, making decisions that affected the lives of billions of people around the world with very little accountability. That made mainstream news organizations feel that this should not be covered like a trade press anymore. The posture of the tech press toward the tech industry should not be that of the aviation press covering the aviation industry. It should be much more like how we would cover oil and gas companies or pharmaceutical companies or Wall Street banks, where you have this very aggressive accountability journalism taking place. So over a period of a couple of years, accelerating after the election of Trump in 2016, there was this push by mainstream news organizations to treat tech as just another industry.

That made a lot of people in the tech industry very, very upset because they would say, "A couple of years ago, you would write up my funding round, but now you only want to write about when we screw up." Or, "You used to cover earnings at my company, and now you only cover scandals." That is true, by the way. There's been a shift in what mainstream publications choose to cover about technology. For a lot of people in the industry, that scanned as needlessly oppositional, antagonistic, etc.

But another factor here is that tech news, just like every other news vertical, had to adopt the practices of social media distribution. "Oracle reports strong second quarter revenue" is not going to get a lot of clicks and shares and views on a web that is intermediated by social media networks. That is not a clickbait headline. Whereas something about a scandal or some executive's fall from grace—

Jasmine Sun (59:18)

"Sydney told me to divorce my wife."

Kevin Roose (59:20)

—or "Sydney told me to divorce my wife" is going to get a lot more traction on that kind of internet. So there's also a structural force that just meant that all journalism had to get more sensational in order to survive. That was not because journalists wanted to do that kind of coverage; that was just how you paid the bills.

But I don't think that sufficiently explains the hostile attitude of many in the tech industry toward the tech media. Whenever someone complains about this to me in the Valley, I try to take it seriously. But I also think if these people knew how much scrutiny the average member of Congress gets, they would be feeling pretty great. Americans and the American press have a long history of very aggressively covering folks with lots of political power. That has not often been applied to people with lots of social and economic power in tech. But I would love to have those tech CEOs who think the media is all mean to them switch places for a week with a backbencher congressman and then tell their friends how the tech press is quite friendly to you compared to what those people deal with.

But you answer the question, because I have motivated reasoning here. I'm not unbiased. Why do you think the tech industry hates the tech press so much?

Jasmine Sun (1:00:45)

When I talk to journalist friends, there are these things you talk about like a tradition of holding power to account. Or if you don't clarify, conversations are automatically on the record, and things like that. With Silicon Valley, I don't think "This is a tradition and this is how journalism works" is a compelling argument. It doesn't make sense to people why if you don't say something's off the record, then it's on the record. It doesn't make sense to people why just because someone is powerful, we should be scrutinizing their personal lives and social media activity. A lot of these norms don't really resonate.

I do totally buy the explanations around clickbait, and I do think that once you get powerful enough, people should cover scandals and when you fuck up. That makes a lot of sense to me. But I also do think that there are just times when journalists are exercising motivated reasoning themselves and do not like technology, and write stories that skew hard against tech to overemphasize mistakes, overemphasize flaws, to characterize things as more evil, more racist, or whatever than they are. That leaves a really bad taste in people's mouths.

Also, my sense is that DC people and maybe New York people are pretty savvy when talking to journalists. There's this thing that happens in Silicon Valley with young founders who have a first conversation with a journalist, and they're way too open. They say all sorts of stuff. It gets written up in an unflattering way, and then they feel betrayed. That feeling of surprise because they don't understand media norms really gets to them, and they're like, "You betrayed me on a personal level. How could you do this to me?"

But I don't know. It's interesting and frustrating, because as I try to do more journalistic work, I can sense the guard people have when I interact with them that is different from how they treated me before I freelanced. They didn't mind when I was a Substacker. They're all cool with Substackers. But as soon as I have one piece in a mainstream publication and I'm part of the "lamestream media," people are a little bit on guard, and it's kind of weird. It feels like I'm trying to repair trust that someone before me broke. I'm willing to do the work because I believe in what I do, and I believe that I'm representing people accurately and in good faith—with rigor and skepticism where it's deserved, and with praise when it's deserved. I'm okay doing that, but I just get the sense that people have a lot of weird scars that I don't understand.

These days when I talk to people in AI, I'll ask, "Do you think there are journalists who are really getting AI right? Who do you read?" Every single time, they think about it. Then they say, "To be really honest, I don't read any journalists. I just read blogs." They read blogs or Twitter. Part of that is the talking up, talking down thing. They want people who are in the weeds with them. But it seems like a bummer. It seems bad.

Kevin Roose (1:03:52)

It's not good. I mean, I think I'm more alarmed about this after hearing your experience because you're newer to this than I am. The pushback from executives has always been there; no one likes being covered negatively. But writers and creators actively resisting the label of a journalist seems bad for journalists. I'm not particularly attached to any sort of label on my own career, but I think that there is a profound failure to communicate the value of journalism by journalists.

Jasmine Sun (1:04:34)

And as you said, it is beyond tech.

Kevin Roose (1:04:37)

I'm a big believer in turning the cathedral inside out and showing people how journalism is made. There were these studies commissioned by the New York Times where people would see things like the dateline—when you have a story and it says "Kandahar" or "Seoul" or whatever, that means that the reporter is literally in the place doing the reporting—and readers had no idea that's what that meant. So there are just a lot of conventions and received wisdom about journalism that I don't think we've done a very good job of explaining to people.

I was thinking about this as I was listening to Pablo Torre's recent series of podcasts. He's an ESPN reporter. I'm not a sports guy, but I had to listen to it because it’s this excessively detailed investigation of a scandal involving Bill Belichick and his much younger partner. He goes into very painstaking detail about how he tracked down these people and these sources, and how he actually went to the place where this mysterious Ring camera footage was found. It was almost funny how much overkill it was in pursuit of this relatively trifling story. But I thought, "This is actually teaching people what journalism is." We should do much more of that as an industry about much more serious stories than Bill Belichick's girlfriend.

Jasmine Sun (1:06:12)

I really like that. I don't care about Bill Belichick and his girlfriend, but I might check the podcast out just to hear how he does that.

I see my Substack as an opportunity to peel back the curtain on reporting. I can do first-person editorializing: here's why I started thinking about this, here's why I care about that. But I notice that people don't understand things like the dateline. Actually, I didn't even know that’s what it meant; I thought it was just a cute quirk.

The other one that gets me is that people don't know the difference between reporting and commentary. It was never a perfect line, of course. Sometimes journalists use news to launder an opinion, and they report out a skewed piece. But I had this conversation with a smart friend who was like, "What do you mean commentary Substacks aren’t journalism?" And I'm like, "Well, they’re not revealing new facts. They're describing and contextualizing other people's facts." He didn't get it, so I tried to explain that there used to be a separate news section and opinion section. But I don't think he registers the difference between a news article, a blog post, and an opinion story when he sees them on the internet on his phone. That's probably true of most people.

Kevin Roose (1:07:46)

Yeah. I run into this all the time. Routinely, if I'm interviewing someone, especially someone who participates in the creator economy, they'll ask to be paid. When I explain that we don't pay for interviews, it's the first time they've ever heard that. I guess they're just assuming that everyone who appears quoted in the newspaper is being paid.

So there's a basic lack of literacy. But I hesitate to put all of this on the consumer because I do think that journalists have profoundly failed at explaining what we do and how we do it to people, including the distinctions you're making about news and commentary. There is so much news that is laundered commentary. There's so much reporting going into commentary. This is not the institutional posture of the New York Times, obviously, which has a very separate opinion section. But I'm a columnist in the newsroom, so I'm allowed to have opinions, but other people in the newsroom are not allowed to have opinions. It's all quite confusing, and I am not blaming people who don't understand all of the arcane byways and rules because journalists don't make it clear to understand, and sometimes we don't even understand.

New media models

Jasmine Sun (1:09:09)

What are the new media models that you are excited about? Are you a Technology Brothers Podcast Network listener?

Kevin Roose (1:09:18)

I like TBPN; aesthetically, I think it's quite clever. I have mixed opinions about the vaguely self-congratulatory, definitely softball-skewed interview style. Interesting interviews can come out of situations where fans of the tech industry interview leaders in the tech industry, or people interview their own colleagues or whatever. You can get good things out of those, but often a little friction, a little tension, or a little opposition goes a long way in making something fun and interesting to listen to.

I think Dwarkesh is doing a really good job with his podcast. I'm also YouTube-pilled. Media organizations should be spending way more time and money trying to crack YouTube. I could do without the AI hype channels where people are just like, "The new Claude just came out, and it will blow your freaking mind, dude."

Jasmine Sun (1:10:33)

Wait, what are you watching on YouTube? Because I don't get anything tech-related there. I only watch cooking videos and Architectural Digest tours.

Kevin Roose (1:10:41)

Really? There are all these hype guys doing their own spin on, "Here's the latest and greatest thing that came out, and you should know about it." Marques Brownlee is truly a generational talent. It's a shame that there are so few tech journalists taking YouTube seriously as a medium for first-party creation. A lot of people, including me, will put clips on YouTube, or I have a podcast, and it goes on YouTube. But if I had a clone of myself, that clone would spend the next year trying to figure out what to do on YouTube.

YouTube is also not a great space historically for journalism. A big part of public misunderstanding about journalism stems from the fact that YouTubers don't follow any of these rules, right? They're constantly doing paid content, sponsored content, payola stuff, pay-for-play. Most of them are not doing what I would consider journalism, but there's a generation of people who have grown up watching them, and for whom that is synonymous with journalism. It all blends together in one big soup.

This is free alpha that I'm giving away, but cracking YouTube in journalism would be one of my top priorities if I ran a big news organization.

Jasmine Sun (1:11:59)

You do have to optimize for each platform and format distinctly. You can tell when a creator is half-assing it. I'm half-assing YouTube right now. I post stuff, but I'm clearly not making things YouTube-native in the way I should. Creators often try to repackage the same content without paying attention to the unique platform dynamics of different spaces.

There’s another hot take that I wanted to ask about. When we did the proposal for this AGI book, you said it might be your last nonfiction book because nonfiction books may not survive AGI. What the hell's up with that?

Kevin Roose (1:13:16)

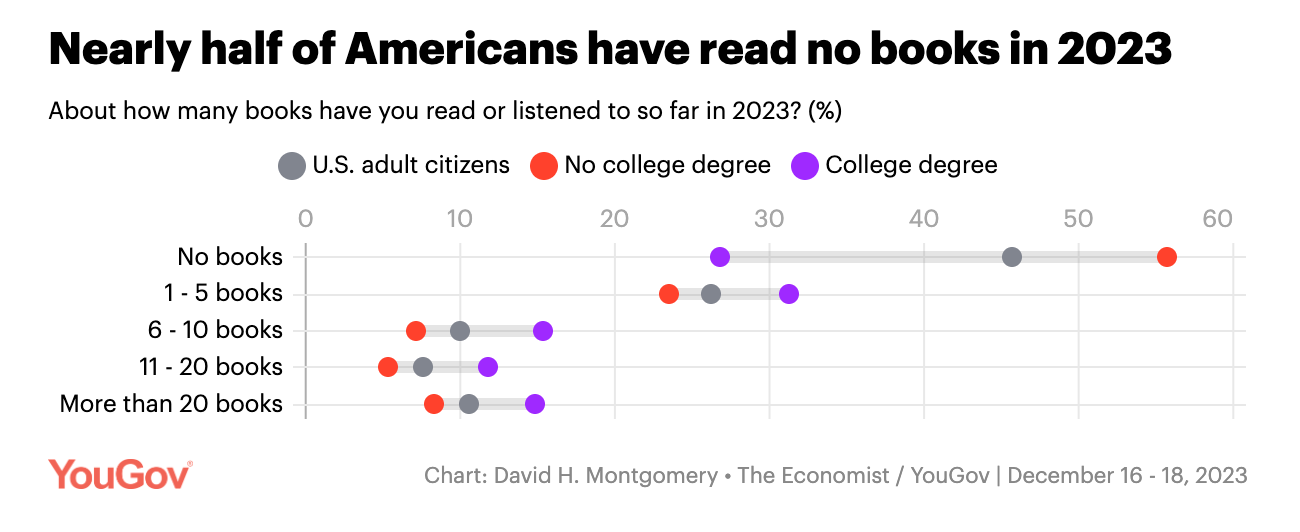

The strong version of this take, which I only about 60% believe, and which I mostly say to get a rise out of people who work in publishing, is that no one has actually read anything longer than an Instagram caption since 2021, and they're just lying about it.

Books have never been a mass medium. If you wanted to get an idea across, you would put it on TV or put it in a newspaper. A subset of Americans has ever read more than a couple of books a year. But today, the number of people who primarily consume information via books rounds to zero. Now, there are still plenty of reasons to write a book. Writing a book allows you to go on podcasts and TV shows, to talk about your idea, or go on speaking tours and make money that way. Professionally, it stamps you as a journalist of a certain seriousness.

But I think the value proposition of books has been weak for a while and is falling. I hope that my book will be the exception and that I shouldn't have just written a series of Substacks or something. I mean, one other thing that books still have going for them is durability, right? I still hear from people who are picking up my first book, 15-odd years later, and are experiencing it for the first time. That doesn't happen with news articles that I wrote 15 years ago. So there's a certain durability to books, especially for people trying to make sense of something that happened in the past.

But if the goal of media is to reach a big audience with an idea or some observations, it's hard to make the case that nonfiction books are the way to do it. The consumption experience is also just radically changing. A lot of nonfiction books now sell more copies in audiobook than in either hardcover or ebook. That's not an accident. Books, ebooks, things that you have to see—they are competing with every other form of visual media. They're competing with TikTok. They're competing with Netflix. They're competing with YouTube. They're competing with your group chat. But audiobooks are different. You can listen to them when you're doing something with your eyes and your hands, in the car or while folding laundry. So I almost classify them as bad podcasts rather than books.

But we are starting to see all these studies about how kids in college today haven't read a full book or can barely make sense of a Dickens story. That's real, and that's a trend that I'm worried about, that I see coming, and that I see AI exacerbating. If you are a person who wants to learn about the bond market and you're coming to it cold, you can get up to speed a hell of a lot faster talking with an AI model, asking for a couple of deep research reports, asking it to summarize everything that's ever been written about the bond market and put it in an easy bullet point list, than you can by reading a book start to finish.

I am saying that this may be my last book in part because I worry that we are moving into a post-literate age. But also, there are probably easier ways to communicate ideas.

Jasmine Sun (1:15:58)

One thing that was really interesting to see was when I was reporting out the vibe coding piece, I got on a Zoom with my friend Hudzah. His finals were the next day, and he hadn't been to any of his classes—not a single lecture. So he took the textbook and papers for each class and put them it in Lovable, asking it to "Make me an interactive website to visually demonstrate celestial mechanics” or something like that. “Give me a set of quizzes that will work me up from the basics to advanced accounting mathematics.” So he never personally interfaced with the papers or the textbooks. He would just shove them into an LLM and be like, "Put this in the format that works for me, and ramp me up way faster than if I had to read the textbook page by page." Afterwards, he updated me: "Passed all my finals." It was clearly working. When I see that, it's hard to way, "Well, you should read the textbook." It’s not like I was reading my textbooks in college.

Maybe next year we can take whatever draft we have of our book, dump it in a language model, and it automatically creates a documentary complete with deepfakes of Sam Altman and whoever. People can then slice up our book into 10-minute YouTube videos that do a reenactment of every scene in there. Maybe that's how some people will consume it.

Kevin Roose (1:18:27)

I want that, but half the screen is just someone playing Subway Surfers. I want the brain rot version.

Jasmine Sun (1:18:33)

At the election watch party I went to this year, we literally did that. We had the election results on the screen, then someone said they were getting boring and depressing. So we put Subway Surfers on the other side, and I was just focused on Subway Surfers the whole time. I was like, "I can't look at this election."

Kevin Roose (1:18:48)

Incredible. We're so cooked.

Jasmine Sun (1:18:51)

It's hard to know how much to be stressed about the decline of reading because I read books, and how much to be like, "You're just being a Luddite, and you should let people consume things the way they want."

Kevin Roose (1:19:11)

Well, make the counter-argument that non-fiction books will still be desirable 5 or 10 years from now.

Jasmine Sun (1:19:20)

I've mentioned your book's take to a few friends of mine who are really bullish about AGI. Even they were like, "That is a crazy fucking thing to say." That's how I knew it was a hot take, you know? These people think they're automating the economy.

But okay, one thing that has always bugged me about LLMs, is the provenance or authorial voice dimension. I care a lot about people's individual perspectives on how a thing happens. This is the thesis of the influencer-journalist or the creator economy: that relationality really matters. When you interpret a news event, you want an individual perspective. Or when you're learning about historiography—you can read four history books about World War II and get radically different interpretations of what went down and what the causality is. If you have an LLM, it merges all of that into a consensus view. One, that is less resonant because people want to know your take on World War II in the context of your broader identity and worldview. Two, it collapses the idea that there are competing interpretations of things.

Kevin Roose (1:20:48)

To be clear, I think that individuals making things in their authorial voice will still be a thing five or 10 years from now. Not books. Why do you have to print it out? Most books should be articles, right? There's that old thing about "Most books should be articles, most articles should be tweets, most tweets shouldn't exist.”

Jasmine Sun (1:20:51)

But the more time you spend with something, the more memorable it is, right? The movies I’ve watched were more affecting to me than the 10-minute YouTube videos, which were more affecting than the 30-second TikToks. If your Wall Street book had been an article, I don't know if I would have been like, "Okay, Jasmine, you cannot take that finance interview." I needed to make my way through 300-plus pages of these kids grueling through their 100-hour weeks and being tormented by their bosses and collapsing of exhaustion for me to be like, "Fuck, do something else with your life."

Kevin Roose (1:21:45)

I would also just say I think you are an extremely, unusually literate person. I'm just looking this up. This is from 2023: 82% of Americans read 10 or fewer books in 2023. Almost half of Americans did not even read one book. So we have to keep the overall context in mind that all the people opining on the future of literacy are themselves part of a very small group of Americans who still read books. Consider the denominator.

Jasmine Sun (1:22:07)

That's true. I think you're right. I did get at least two of my friends to also read that Wall Street book, and it convinced one of them similarly to not go to Wall Street. So you had n equals at least three impact.

Kevin Roose (1:22:36)

Thank you. That is very important to me. I hope I am wrong and that nonfiction books continue to be a lucrative and successful medium well into the future.

AI lightning round

Jasmine Sun (1:22:41)

We're almost out of time, so we can do AI as a lightning round, especially because we both talk about AI enough elsewhere.

Your third book, Futureproof, is about how humans can automation-proof themselves. It was published in 2021, right before the world woke up to LLMs. Most of it focuses on predictive algorithms, not generative AI. Language models were kind of a thing, but not really yet. Now we are writing another AI book.

What was the first moment that you realized that AI was a huge deal?

Kevin Roose (1:23:28)

When I went to Davos and heard a bunch of CEOs talking about their plans to replace most or all workers with AI.

Jasmine Sun (1:23:36)

When did you realize that AGI was a huge deal?

Kevin Roose (1:23:38)

When I had a conversation with Bing Sydney.

Jasmine Sun (1:23:42)

Are you still worried that AI is going to automate all of our jobs?

Kevin Roose (1:23:46)

Not all. Maybe most.

Jasmine Sun (1:23:48)

What is one big way in which your beliefs on AI have changed since Futureproof?

Kevin Roose (1:23:55)

My timelines have accelerated dramatically. I thought we had 10, 15 years probably to prepare.

Jasmine Sun (1:24:03)

And now you think we have 3?

Kevin Roose (1:24:06)

18 months, maybe.

Jasmine Sun (1:24:07)

Which of your 2021 beliefs on AI has held the best?

Kevin Roose (1:24:13)

The importance of craft and taste.

Jasmine Sun (1:24:16)

Are you more optimistic or pessimistic about human agency over AI now?

Kevin Roose (1:24:24)

I'm more optimistic.

Jasmine Sun (1:24:25)

Why?

Kevin Roose (1:24:25)

I think we'll pull this off somehow. I don't know exactly why, but my p(doom) is only 10%. I guess that qualifies me as an optimist around these parts. I'm a humanist. I believe in humans and our ability to overcome challenges. I think that if and when AI becomes a threat to our ability to flourish, we will stop it or transform it or do something to keep ourselves in the driver's seat.

Jasmine Sun (1:24:54)

What's your p(consciousness)?

Kevin Roose (1:24:55)

5% right now. That's just a vibe.

Jasmine Sun (1:24:58)

That's higher than I thought it was going to be. My p(consciousness) is 1% right now.

Kevin Roose (1:25:06)

Maybe I'm too high.

Jasmine Sun (1:25:08)

I mean, I didn't talk to Sydney.

Kevin Roose (1:25:10)

I'm not a theory of mind specialist. I'm not a moral philosopher. I don't know what makes something conscious or not. I have a somewhat functionalist view of this stuff. If you had shown GPT-4.5 or Claude 4 or Gemini 2.5 to me back in 2020, I would have said, "Yep, that's AGI."

Jasmine Sun (1:25:37)

How are you currently AGI-proofing your own career?

Kevin Roose (1:25:42)

I think podcasting is more AGI-proof than writing. So that's a good move on both of our parts, I think.

Jasmine Sun (1:25:48)

How are you AGI-proofing your son?

Kevin Roose (1:25:51)

I don't know. He's only three. So I feel I have some time before he needs to go out and make a living. But I talk about this all the time with my wife, and with our other friends who are parents of young children. I do not know what education looks like when he is old enough to go to college. I don't know whether he will go to college. I don't know what jobs there will be when he goes to college, but I just want him to enjoy being young and not think about this stuff for as long as feasible.

Jasmine Sun (1:26:29)

Damn. I have to be on a panel about AI and parenting in 4 hours. I was hoping you were going to give me the answers.

Kevin Roose (1:26:37)

I'm sorry, I don't have them. If you figure them out, let me know. There'll be a lot of parents on my WhatsApp group eager to hear about it.

Jasmine Sun (1:26:40)

What's something in AI that you disagree with most of your journalist peers about?

Kevin Roose (1:26:48)

I think that hallucinations are not as big a deal as my peers think.

Jasmine Sun (1:26:58)

And what's something you disagree with most AI researchers about?

Kevin Roose (1:27:02)