🌻 are you high-agency or an NPC?

AI anxiety and the new lexicon of silicon valley

The AI gold rush has sparked a vibe shift in San Francisco. The city is flush with money again after the post-ZIRP recession of 2022. Cracked 22-year-old coders are telling the world they’re going to “solve hurricanes” and the "national debt.” Lurie is mayor, nature is healing, the technology brothers are back with a vengeance. Take a look—$100 million salaries, glitzy hype videos for fundraises, lavish parties with dress codes—Silicon Valley is swelling with Trump-era opulence—blustery, spendy, and male.

It is easy to think from the outside that San Francisco is the one place on earth insulated from crisis. Everyone else is living in fear of political upheaval and mass job loss, while the rich nerds discovered suit jackets and now they’re the ones on top. “My mutuals run the world,” goes one Twitter refrain.

For the tech industry as a whole, this may be true. But for most individual participants, the swagger is a gilded surface, paper-thin. To make an analogy: while most English-language headlines about China emphasize its industrial might, some observers have turned to internet anthropology as a way to find cracks in the story. Social media slang like 996, tangping, laoshuren, and involution point to the slice of urban youth who feel they are getting crushed by the development machine. Humor is a release valve for what you can’t say.

Likewise, read between the tweets, and you’ll find an uneasy blend of ironic zoomer nihilism and a triumphant tech bro resurgence, big-mouthed hustle-posting with an undercurrent of AI status anxiety:

Are you a live player or a dead one?

Are you high-agency or an NPC?

Do you think you’ll escape the permanent underclass?

For fun, I decided to deconstruct the linguistic memes that dominated the Twitter-waves this year.

Agency

There’s a bit of self-help for nerds that goes “intelligence is getting what you want.” You can be a top-ranked competitive coder or know every world leader’s birthday by heart, but the only real metric of success is whether you can build a life you’re happy with. Cold-emailing your way into a dream job is pretty high-agency; quitting it to become a strawberry farmer is even more so. Agency is initiative, resourcefulness, a high internal locus of control. Not stressing about roadblocks and assuming you’ll figure it out along the way.

Economic “agents” maximize utility under constraint. Sutton and Barto, fathers of reinforcement learning, swap utility for “reward,” giving examples of a chess player making a move or a cleaning robot optimizing its path. In each case, the agent “seeks to achieve a goal despite uncertainty about its environment.”

In real life, agency and ambition go hand in hand. Just as young Demis Hassabis mastered the Pentamind—a competition that awards games players with general ability, who trounce opponents across Sudoku and Go and poker and more—a capable agent should be able to enter any terrain, and with enough trial and error, develop a strategy to succeed.1 In 2008, Paul Graham wrote of Sam Altman: “You could parachute him into an island full of cannibals and come back in 5 years and he’d be the king.”

While a pocket of tech elites have been using “high-agency” since the mid-2010s, it’s no surprise the term has taken off amid the LLM boom. Given access to a system that’s memorized all documented human knowledge, what matters is not expertise, but a dogged ability to adapt and win no matter who you are and what you start with.

As Meghan O’Gieblyn writes in God, Human, Animal, Machine, human exceptionalism is a stubborn beast. We prize ourselves not on a fixed set of traits but on having whatever other beings don’t. For ages, smarts were what separated man from his fellow mammal. Cheetahs may have speed and chimpanzees strength, but inventing fire and writing was what put humans on top.

Now, LLMs are toppling traditional intelligence benchmarks one by one: the Turing Test, then the LSAT, then the IMO Gold. They can answer PhD-level economics questions and creative writing prompts. But today’s computer-use agents can barely share a Google Doc without human intervention. LLMs can draft an essay pitch but not come up with the concept, give you a recipe for a bioweapon but not the savvy to acquire the ingredients. If agency combines autonomy (“the capacity to formulate goals in life”) plus efficacy (“the ability and willingness to pursue those goals”), AI in 2025 is sorely lacking in both.2

It turns out the secret of human civilization was not any particular cognitive creation but our unending flexibility. To hit a wall and build a ladder to climb it, to design cars instead of faster horses, to come up with new levels of Maslow’s hierarchy to summit once we’ve satisfied the first.

In the next two years, things could change. Many are capitalizing on what they view as a narrow window where AI has obsolesced most IC work but not entrepreneurship itself. For now, agency is still a human moat.

Related terms: founder mode, live player, you can just do things

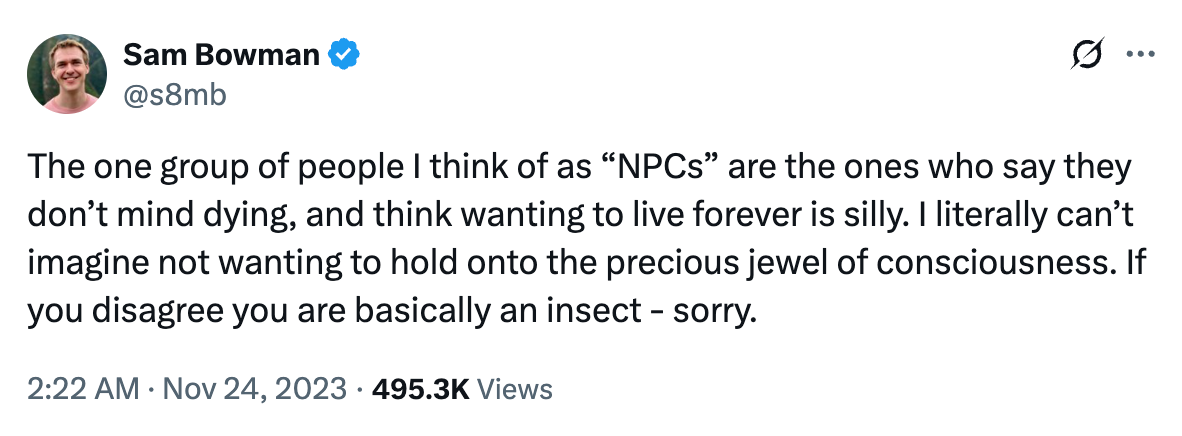

NPC

The opposite of an agent is an “NPC,” or a “non-player character.” This term, too, has roots in video games, where NPCs are background characters whose actions are hard-coded by game designers. Smiling shopkeepers, gossiping villagers, battlefield casualties who are counted but not named—NPCs provide rich settings for player characters to act without the ability to pursue quests of their own.

NPCs start every morning with Starbucks and the Spotify algorithm. They’ve worked the same Big Tech job for the last 7 years, collecting a 5% annual raise and spending it on a surf trip to Hawaii. The NPC always votes Democrat but doesn’t know why. Hobbies include Netflix and “trying new restaurants.” Sometimes, they scroll the app Threads.

The NPCs don’t know that AGI is coming. The NPCs will probably end up stuck in the permanent underclass. The NPCs go about their quiet lives, playing LinkedIn Games and watching Marvel movies, blissfully blind to the technological tsunami mounting behind them.

Related terms: normie, wagie, sheeple, bot

Permanent underclass

This summer, my Twitter algorithm was dominated by talk of escaping the “permanent underclass” and the “great lock-in” of September to December 2025.

These are mostly jokes, of course. But they express young tech workers’ latent anxiety about who will win and lose in the age of AGI—or at least, the assumption that there will be winners and losers, rather than AGI bringing about widespread abundance in a massively positive-sum game. Even the people building AI don’t feel insulated from precarity. Nobody knows if they’ll end up above or below the API: whether you’ll be the automaters or the automated. And despite CEOs’ attempts at optimism, I hear the “gentle singularity” and “personal superintelligence” deployed more often as punchlines than earnest visions of utopia.

There are good reasons to expect inequality to get worse. AI increases returns to capital rather than labor; the more money you spend on compute the more robot labor you can rent. (Consider the cost of running 100 simultaneous ChatGPT queries or Claude Code requests.) AI also loosens the link between profits and payrolls, breaking the interdependence between rulers/citizens or owners/employees that give the masses leverage against their masters.3 An essay by Luke Drago and Rudolf Laine describes this dynamic as the “intelligence curse”: much like the resource curse entrenches autocracy in oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia, a US economy that no longer needs as many people to generate wealth will have much less incentive to take care of their needs.

Then there’s the fact that we’ve never had consumer products this cheap and addictive before—Nozick’s experience machine is real and it looks like TikTok. I think of Zuckerberg’s comment that “The average American has fewer than three friends, but demand for something like 15.” The nightmare goes like this: as digital relationships become more accessible, partying/marriage/fertility rates will continue to drop—making in-person socialization a rarefied luxury good. The permanent underclass will be sedated and dopamine-hacked by hyperpersonalized AI lovers, too wireheaded to have agency in the post-AGI age.

Related terms: NEET, below the API

996

As with shortform video, hard tech, and carceral urbanism, San Francisco is a decade late to the Chinese phenomenon of 996: a work culture of 9am to 9pm, 6 days a week.

At some point this year, SF startups started loudly advertising their insane work hours. Gone are the halcyon days of camera-off Zoom standups and PM pool girls. A new generation of zoomer-led startups like Krea and Mercor are taking after Elon Musk (who somehow retains much of his pre-DOGE halo), boasting about weekend grinds and sleeping bags in the office.

I’ll first mention that Chinese 996 involves bathroom surveillance and ICU trips, while a good chunk of SF 996ers are hitting Souvla and Barry’s on company time (if I spot your name on every Partiful, you’re not really 996ing).

Posers aside, many 996 acolytes insist they’re accumulating wealth before AGI comes, that the crazy hours are driven by crazy competition, or that it’s all for pure love of the grind. There’s some truth here but I think the “trend” is mostly just signaling. Neo-hustle-culture is a modern twist on Weber’s Protestant ethic: if the world is soon to be divided into the blessed and the damned, the techno-kings and the techno-peasants, anxious technologists should work as hard as they can to prove they deserve to end up on the right side of that divide.

Plus, it’s not like the AIs are taking Sundays off.

Related terms: chinese century, 007, the great lock-in of September to December 2025

Taste

The current consensus is that Rick Rubin is the most human human to ever live. In a world where intelligence is too cheap to meter, what matters is not skill but knowing where to direct it.

“Research taste” is about naturally intuiting the most impactful problems to work on; “high-taste testers” are what OpenAI calls the power-users they ask to qualitatively assess model vibes (presumably, low-taste testers are the unwashed masses, relegated to mere thumbs up/down votes). Marc Andreessen proclaimed that the “taste element” means VC is the one job that can’t be automated: “It’s not a science—it’s an art.”

All this taste talk has set off a minor arms race to prove that you have it. Founders show off their “taste” with garish high-end swag and pretentious company names like “The X Company of Y.” Suddenly, SaaS startups are hiring “storytellers,” documentary filmmakers, print magazine editors. They are throwing soirées with Luma waitlists and advertising enforced gender ratios, no work talk, you can keep your shoes on. Paradoxically, the same people who talk the most about taste seem the most preoccupied with social norms.

But the Taste Guy is just the Idea Guy reinvented for the attention age. It’s trading meaning-making for trend-hopping and cosplaying success instead of earning it. It’s posting slick prototypes for Twitter views instead of real products for DAUs and cash. It’s the fantasy of a post-AGI world where you don’t need to learn to code or write or sell because you’ll just hand the agents your brilliant high-taste business plan—I’m more of a creative than an operator—and let them do the rest.

I am a traditionalist who believes that taste does not exist in a vacuum. Expert judgment only seems automatic because it channels the 10,000 hours of reps they’ve done before. In fact, AI may soon have better taste than you because it’s trained on that data. Humans, well, you better study up.4

Related terms: intersection of art and technology

Decel / doomer

I gotta hand it to the e/accs: “decel” is a beautiful turn of phrase. It effortlessly links “decelerationist” to the reviled “incel,” making it a perfect all-purpose slur for anyone advocating more than zero tech regulations or who’s unwilling to raze a neighborhood in service of a new chip factory.

“Doomer” has even made it into Trump admin vernacular. NVIDIA lobbyists are tarring export controls advocates with the label “doomer science fiction”; White House AI czar David Sacks declared in August that “The Doomer narratives were wrong”—no apocalypse in sight. (AI safety folks wish they had a slur half as sticky.)

There are many warring Silicon Valley tribes these days—tech right, abundance, network state, whoever—but they all share the same big three meta-narratives:

Technological advancement is the root driver of historical progress, from economic growth to social liberalism to geopolitical dominance. If a society fails to lead in science/tech, it will decline.

Empowering brilliant, outlier individuals is the key to success. They can be founders, scientists, or operators—and valued for intelligence, agency, or sheer drive—but must be free from bureaucratic or collective control.

Markets are the most effective system ever created—for innovation (e.g. startups), truth-finding (e.g. prediction markets), talent (e.g. immigration), and anything else. They allow the best to rise to the top.

But decels and doomers are pessimistic about tech, markets, and human ingenuity—instead petitioning for bureaucrats to slow it all down. They’re staging hunger strikes outside of AI labs but too soft to make it two weeks. Thus, it’s the lowest-status thing a person can be.

Related terms: e/acc, low-T

Low-T

There’s some weird gender and health stuff going on in SF that I don’t fully understand yet. More research required, TBD, let me know if you get it.

Related terms: birth rates, low-agency, nighttime erections

The other night, a friend and I are at a meetup in the Russian sauna, dissecting the city’s frenetic “gold rush vibes.”5 There’s a way that living here makes money feel immaterial. Everyone is hooked up to an infinite money machine—post-exit founders, Google ad rev, sharky VCs, any early employee at an AI lab—and they’re all at the same banyas and house parties and overpriced coffeeshops as you. Earlier I walked into a steam room where I can’t see anyone’s faces, and eavesdropped on a debate about GPU procurement. In the hot tub, a young man asked, incredulously, Is anyone really making these crazy AI salaries? I think ****** is worth $300 million, his friend replied.

That’s the thing outsiders don’t get. Inequality of course exists between RV dwellers and FAANG engineers, but also between those same engineers and their post-economic peers. A VC once insisted I was “lower class” for earning $180k a year, then griped that he got invited to party weekends in Greek villas but couldn’t afford to throw them himself. At a book club, a young man confessed that his OpenAI bonus will only net him an extra $300k (shamefully, he didn’t make the $1 million tier). When everyone can meet their basic needs, money dissolves into pure status competition.

Politics talk is kind of for losers, too. No one talks about ICE or Gaza or the Epstein files, with exceptions for YIMBY discourse and H1-Bs. At a tech right happy hour, a man implored the audience to move to DC to contribute computer skills—as if DOGE had never happened, as if public service were still a clean and uncomplicated thing. I don’t know if it’s disinterest or superstition or a sense of invincibility: We’re all techno-optimists, we aren’t supposed to feel fear. Acknowledge the precarity and you might make it real.

Back in the sauna, the temperature is climbing. We hold our heads in our hands, trying not to overheat. There’s a stinging on my collar and I realize I forgot to remove my necklace. A first-timer burns the soles of his feet. Finally, I’ve had enough. We file out, and plunge into cold water.

Hope you’re all doing alright, and thanks for reading. I’ve been quite distressed and distracted by the Political Situation lately but still figuring out how/whether to write about it, if folks have advice. In the interim, am trying to touch grass and be in the real world more.

—Jasmine

Sometimes I think of the LLM and RL schools of AGI as two theories of intelligence. Is intelligence about being able to answer any question, or being able to achieve any goal? Now that we’ve conquered the former, attention has turned to the latter mission.

It’s interesting to contrast economic and philosophical definitions of agency. The former emphasizes a strategy for utility maximization, whereas the latter requires underlying beliefs that drive action. I like Henrik Karlsson’s explanation because it couples them. jessica dai makes a similar distinction in her paper on “mechanistic” vs. “volitional” agency, arguing that AI only qualifies as a moral agent under the former definition.

This assumes that as AI becomes more general and capable, it will do more automation vs. augmentation (already trending this way), i.e. that it will be more of a substitute than complement to human labor. Though even if AI is an augment, it may likely increase bosses’ expectations of worker productivity.

Also, anyone who has taste in something isn’t going around talking about it in the abstract. If you’re a movie buff, you’ll probably say “I see a lot of movies and prefer X kinds,” not “I have Good Taste™.”

I liked Scott Alexander’s exploration of the “taste” concept here; it reinforces a lot of my suspicions as well.

“Maybe I’ll throw a gold rush themed party,” he muses. “We have the budget, and gotta spend it somewhere.”

Great exploration of what feels like (from a distance) symptoms of a collective nervous breakdown within Silicon Valley—all these obsessions read like explicit and implicit manifestations of anxiety about the ongoing deskilling of coding jobs, the general oversupply of coders, diminishing labor share/power in the industry, diminishing returns to scale in A.I., the total failure of Trump administration, plus all the contradictions already inherent to the industry. At least to me the main thing all this stuff reeks of is total sweaty desperation. Look at my leading industry dawg were all going to die.

I’m a high agency NPC