🌻 america against china against america

notes on shenzhen, shanghai, and more

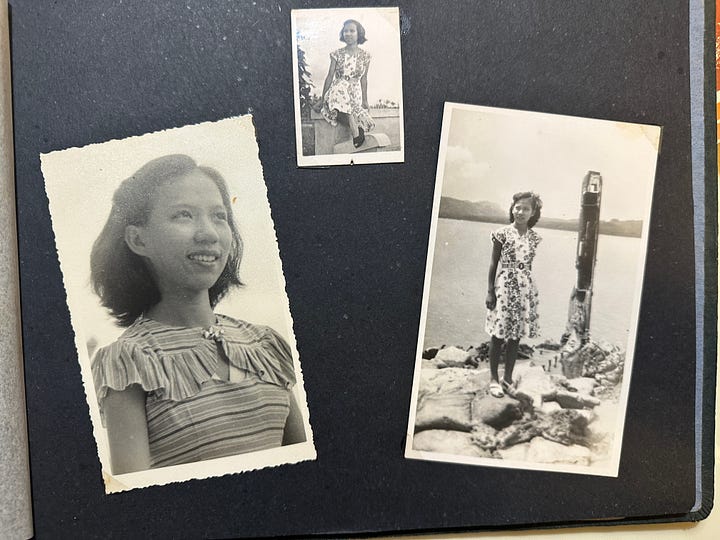

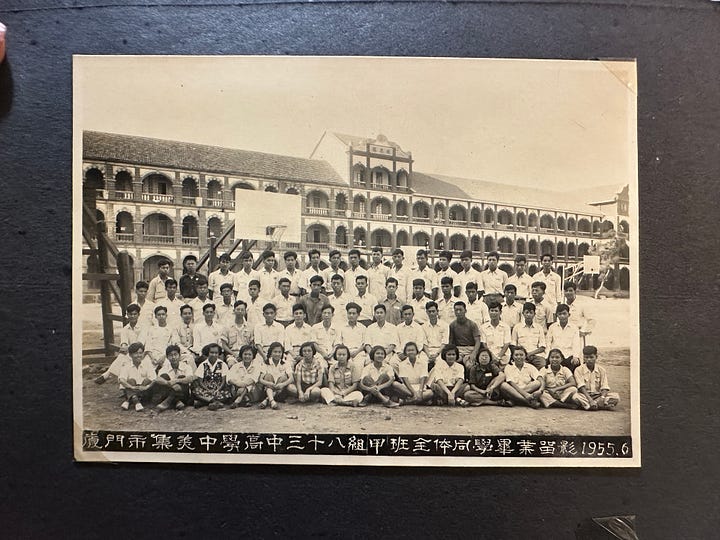

In 1953, my late grandmother left home and embarked on a solo boat voyage to a country she had never been to. Back in Indonesia were her parents and six younger siblings. On the other side was her new high school in Fujian Province, which was established expressly to educate overseas Chinese. The PRC had been founded only four years prior, and they’d started an enthusiastic recruitment campaign to get a generation of patriotic young scientists to help build the new China.

After high school, my grandmother headed to Fudan University in Shanghai to study math. The next decade would be tumultuous. Her mother would pass away, Suharto’s regime would escalate violence against Chinese-Indonesians, and Mao would begin the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. As a university professor with international ties, her possessions were seized, and she was sent to the countryside for “reeducation.” And when mail lines between Indonesia and China were cut, she lost contact with her siblings and family for twenty-odd years.

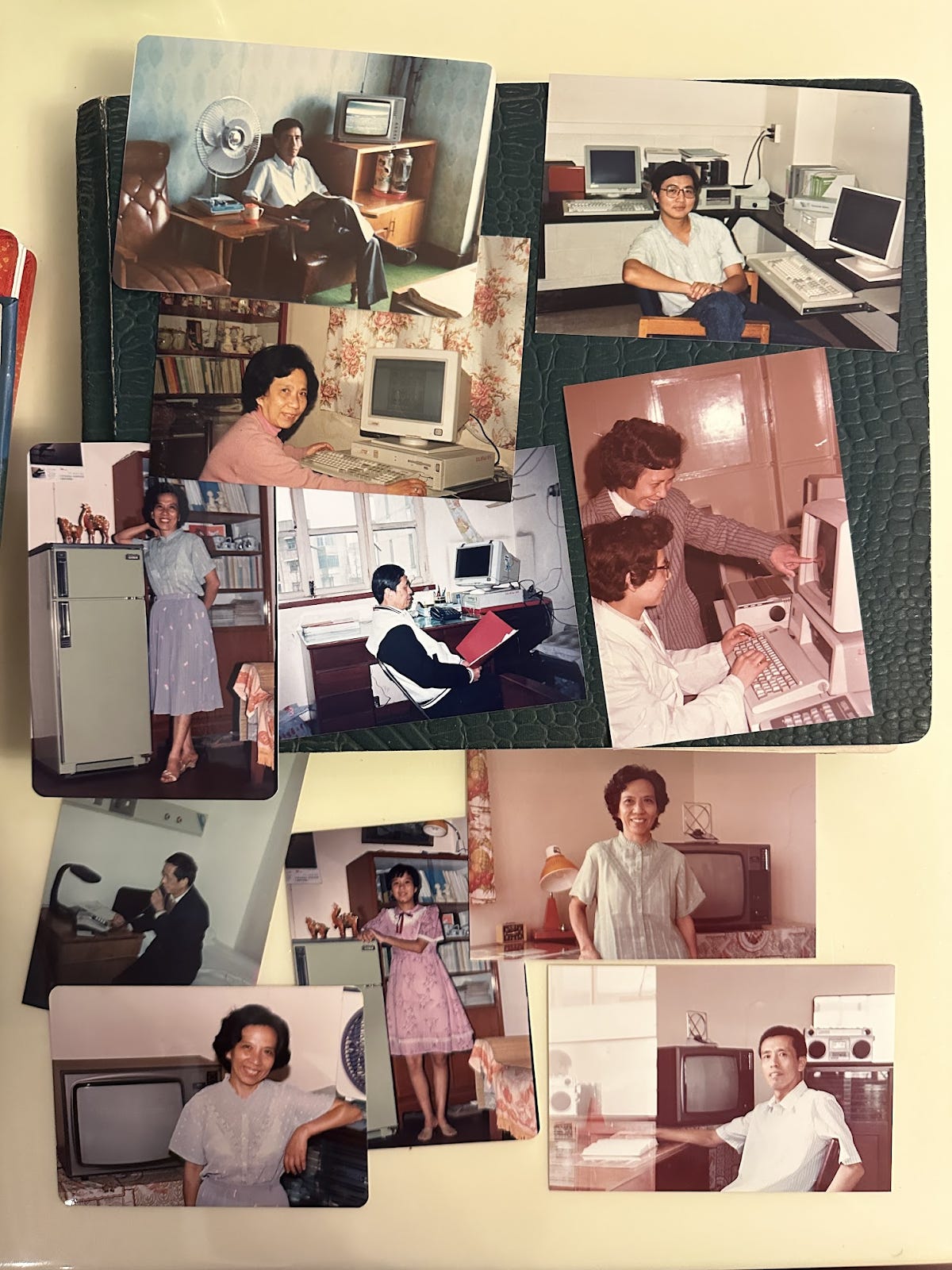

It took until the 1980s for China to fully reopen its schools and borders, and for my grandparents to resume their content academic lives. My favorite photos from this era show them posing with various electronics: fridges, TVs, chunky computers. A new appliance was always a worthy cause for a shoot—tangible symbols of progress and success.

In 1988, fellow Fudan professor Wang Huning won a prestigious visiting scholarship to the United States. He spent six months exploring and writing, ultimately publishing his reflections as a book titled America Against America. Significant portions are dedicated to his analysis of American technology. For instance, Wang marveled at the space program and spirit of invention:

[Americans] are confident that there is always a way, unremitting in their perseverance. That spirit has led them to pursue a great number of extremely bold and daring ideas, such as the Star Wars program and the space shuttle. It also prompted them to embrace many smaller, less eye-catching inventions, such as a machine for opening envelopes, a machine for opening cans, an electric pencil sharpener, and so on.

But as a political theorist, Wang was of two minds. On one hand, he noticed how technology can increase social alienation and a materialistic “money first” attitude. But he also considered how it may tame an unruly society more effectively than law:

Giant strides in techno-scientific development have perfected the means for governing man, possibly breaking through ordinary technological management and penetrating the inner world of every person, infiltrating people’s private sphere. In present-day America, there is generally no power that can break through faith in individualism and the barriers [surrounding] the private sphere. [But] science and technology have this power. They guarantee material rewards, which is another condition [for their success].

Today, Wang sits in the most senior ranks of the Politburo, and is credited for many of Xi’s signature concepts, including the Belt and Road Initiative, Common Prosperity, and even “Xi Jinping Thought.” His philosophy is reflected in China’s approach to tech governance: fierce industrial ambition plus strict social control—both of, and enabled by, technology.

This is a core belief shared by modern China and Silicon Valley alike: Who wins in technology, wins the world.

I returned to China this year first to see my family, and then to travel with friends—Charles Yang , afra Wang, Clara Collier, Aadil Ali, Arjun Ramani—who all hoped to see China’s technological achievements firsthand. We had different levels of experience in China, but all of us are “tech writers” of a kind. We are interested in progress and abundance, in science and economics, in how tech diffuses across firms and borders. We are curious to understand the philosophies, talent communities, and political environments that nurture and stifle innovation. We are committed, also, to humanism: underneath the GDP statistics and geopolitical fights, we want to know how people’s lives actually change.

So in mid-August, we embarked from Hong Kong, then took trains to Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Yuyao, and Shanghai for a few days each. I’m cognizant that visiting a few places for a few weeks will never present a whole picture. But as with Wang Huning’s travelogues, perhaps there’s some value in an visitor’s eye. All narratives are simple from a distance; the hard part is seeing the cracks up close. This essay shares those observations.

Shenzhen was established by Deng Xiaoping in 1980 as a Special Economic Zone, and this history means it is relatively liberal by Chinese standards. (I’ve wondered whether the US West Coast is similar. Being far from the capital makes a big difference.) Most of Shenzhen’s GDP comes from the private sector, unlike in Beijing and Shanghai where bureaucratic SOEs still comprise half, and its reform-minded officials were early to minimum wage laws and expanding hukou to migrants. Everyone is a transplant, and no one is old.

Shenzhen’s rise from mud is impressive, but the city was not planned for human scale. It took 50 minutes by car to get anywhere. We were routinely befuddled by how to walk from the Luohu subway station to our hotel: they were purportedly across the street, but due to the multi-lane road separating the buildings, the hotel was only accessible by navigating a looping maze of under- and over-passes. (For some reason, Chinese really dislike walking—I was shocked by how often people would squeeze into jam-packed escalator lines rather than saunter down an empty flight of stairs.)

There are some strollable bits: skyscrapers and night markets here, an urban hike up to a Deng statue there. I did appreciate the famed electronics market Huaqiangbei, where you can purchase anything from off-brand iPhones to factory cables. (Pro tip: The real discounts are in the tiny stalls a few floors up, and you can always barter on bulk buys. “The ground floor is for chumps,” Afra told me.)

But the state’s shadow is never far. In the stairwells of Huaqiangbei, in malls and in industrial parks, you’d see riot gear—shields and batons—propped against walls, ready to stop a phantom protest at any moment. It’s unclear if these materials—identical in every location and every city we visited—were actually meant to be used (you’d think that theoretical rioters could grab them as easily as police). Instead, they served as an ever-visible reminder that you were never far from the full force of the state.

Our first day in Shenzhen, we met a Chinese AI researcher at Gaga, a Western-style chain cafe that serves avocado kale smoothies and wagyu sliders (plastic gloves provided). He wore a black designer t-shirt and drove a NIO electric car that cost $70k USD. After finishing his master’s degree at a California university, he got married, moved to Shenzhen, and started work in a lab.

“What does a day in your life look like?” we asked. “I wake up and I check Twitter.”

“Do you have to work 996?” “No,” he laughed. “It’s 007 now.” (Midnight to midnight, seven days a week.)

“Do you guys worry about AI safety?” “We don’t think about risks at all.”

“Based,” said Aadil.

This was the first of several conversations that gave us a distinct impression of the Chinese tech community. Spirits are high, and decoupling policies like export controls only fuel their patriotic drive. “China feels bullied—that 100 year scar doesn’t come off. David Sacks is right about chips, but it’s too late now. You can’t slow us down.” After news of the US tariffs hit Chinese social media, netizens adopted the satirical nickname “川建国”: “Trump builds the nation,” or more elegantly, “Comrade Trump.”

Chinese engineers also seem more practical than their American counterparts. They’re here to build tech and make money; risk management is for bureaucrats; policy is only relevant insofar as it helps or hurts your work. This is something I think Westerners often get wrong. If you live in a single-party state, you are, on average, less ideological yourself. The politics have already been decided—no point wasting extra cycles coming up with something new.

Overall, I left my conversations with Chinese technologists feeling real admiration: they faced unimaginable uphill battles from US restrictions and a competitive domestic market. Low margins and a thin capital environment don’t stop people from shipping high-quality work. Sure, such rhetoric could be performative chest-puffing. But their mindset was locked in. One could argue that Chinese are trained their whole lives for this—competition only makes them stronger. As Charles put it: They had the fucking juice.

To be clear, our researcher friend made clear that working at a top US AI lab was still the most desirable option. And within China, DeepSeek is still in a tier of its own. (Not a single full-time employee has left the lab since January, supposedly due to a combination of higher salaries, firm loyalty, and maybe most importantly, a rumored poaching ban issued by premier Li Qiang.) But he didn’t seem too pressed. His job was exciting, and he had AI Twitter and groupchats to keep him in the loop.

No word appeared in conversation more often than neijuan1 (内卷), or “involution.” The term was popularized in 2020 among Chinese social media users, though it was supposedly first adapted by online intellectual Liu Zhongjing (who Afra described as “the Curtis Yarvin of China”) from anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s book on rice farming in Indonesia. Quoting Yi-Ling Liu’s New Yorker piece on the topic:

Geertz’s theory of involution holds that a greater input (an increase in labor) does not yield proportional output (more crops and innovation)... Involution is “the experience of being locked in competition that one ultimately knows is meaningless,” Biao told me. It is acceleration without a destination, progress without a purpose, Sisyphus spinning the wheels of a perpetual-motion Peloton.

Chinese solar companies battling to the death? Involution. High schoolers spending Saturdays out-prepping each other for the gaokao? Involution. Six hotpot restaurants side-by-side on a single mall floor? Involution. Boba delivery that somehow costs less than pickup? Dance, dance, involution.2

Involution initially seemed like a uniquely Chinese phenomenon. But the more I thought about it, the more I noticed involution in modern America as well. AI model providers pouring billions in to outcompete each other by 0.1% gains on benchmarks that consumers will never see, college graduates applying to hundreds of entry-level software jobs to land a single interview, urbanites spending hours optimizing Hinge prompts only to get ghosted by a situationship. A recent piece by Delia Cai argues that American zoomers are “the most rejected generation.” Increasing competition, decreasing returns. It’s no wonder that cynicism starts to set in.

The difference, rather, is who makes the market. In China, this is the state. Declare semiconductors or drones or lithium-ion batteries a national strategic priority, and companies will flow into the space. In the US, it’s private investors. A big VC fund names a thesis—e.g. creator economy, agentic workflows, American dynamism—snaps their fingers, and 1000 near-identical startups will appear like magic. Business follows incentives.

There are trade-offs to each strategy. Governments can think on longer time-scales and prioritize real social utility—hence China’s dominance in, say, green tech. But just because they’re good at picking problems doesn’t mean they’re good at picking winners. In the 1990s telecom wars, the privately-owned Huawei trounced SOEs Julong and Datang despite the generous subsidies the latter received. Today, many wonder whether DeepSeek will end up dragged down by their golden child status. It takes zero Chinese bureaucrats to build a frontier model, but just one to kill it.

We then visited the Tencent headquarters in Shenzhen. The company is something of a hydra. They created WeChat (the super-app to end all super-apps); own Riot Games and Supercell; and make the domestic equivalents of Spotify and Netflix too. (One theme: Chinese companies do not seem to believe in specialization and core competencies, and like to do everything in-house that they possibly can. The level of integration is both impressive and confusing. Perhaps self-reliance reduces dependencies on other firms, insulating from both political and competitive volatility.)

At this point, I’m used to how every Chinese company has a full-fledged exhibition hall featuring a movie theater, framed patent wall, and museum-like artifacts in glass boxes. To my jaded American eyes, the pomp is ridiculous. Still, Tencent’s show was the best I’ve seen. Walls split down the middle and opened as doors. We sat in a nostalgic life-sized recreation of a 2000s internet cafe, where you could browse an early version of QQ Messenger; and tested a slew of genuinely impressive technologies: flight simulators, live call translation, palm-print checkout, and immersive games.

Some rooms bragged about Tencent’s social impact: $10 billion USD spent on carbon neutrality goals, rural education programs, and medical assistance AI. “VALUE FOR USERS, TECH FOR GOOD,” proclaimed their new mission, which Afra insisted sounded better in Chinese. It was like I had been catapulted back to a pre-techlash era where platforms still earnestly talked about changing the world. “Trump is not so into inclusivity now. But here, we still have it,” our Tencent contact joked.

Later, I read that Tencent was one of several big tech companies (including JD.com, Meituan, and Xiaomi) that donated billions to philanthropy in 2021, right after Xi’s Common Prosperity crackdowns. The coordinated timing, analysts note, suggests political pressure rather than pureness of heart.

Still, I’d be lying if I didn’t find the grandeur at least somewhat inspiring. If I were in middle school, I’d feel quite motivated to contribute my technical skills. I felt similar browsing the Mao-era posters showcasing science, spaceflight, and heavy industry at the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Museum. Did the US just need to fill a propaganda gap?

Confucian paternalism still runs through Chinese society. Previously, I would have dismissed this framing as orientalist, but I am increasingly persuaded of the philosophy’s explanatory power.

A teacher told us that for PE homework at her school, parents had to film videos of their kids jumping rope 100 times, then upload them to a class WeChat group as proof. In 2021, Xi limited gaming companies like Tencent from allowing minors to play for more than one hour during the school week. (Many enterprising kids leveraged their grandparents’ face IDs to squeeze in extra play time.) Grown-up civil servants are also measured by how much time they spend on “Study The Great Nation (学习强国)”: the hot new app for Xi Jinping Thought.

In his excellent book The Rise and Fall of the EAST, MIT professor Yasheng Huang frames such mandates within the legacy of the keju imperial exam system. By setting transparent yet highly demanding standards for its students, bureaucrats, and citizens, the Chinese meritocracy directs human capital toward state-approved ideology, leaving no time for independent (and potentially threatening) intellectual endeavors.

China also has its own version of tall poppy syndrome, but in its case, the state wields the shears—Jack Ma being the key example. Idioms like 树大招风 (tall trees catch more wind) and 人怕出名猪怕壮 (people fear fame, pigs fear getting fat) warn the dangers of speaking up or standing out. These norms, my mom theorizes, are one reason that Chinese have not been as successful as Indian Americans in ascending American corporate hierarchies.

We initially decided to visit Hangzhou because of its status as China’s rising AI hub. It’s home to DeepSeek, Unitree, and Alibaba; plus surveillance giant Hikvision, known for its “City Eye” policing system. But we ended up opting for pure tourism instead, ambling around West Lake (famed for its poetry-inspiring beauty, and which lives up to the hype), sipping oolong tea, and luxuriating in a 24-hour spa.

Like other domestic tourist hotspots, there is a reconstructed “Ancient Town” in Hangzhou’s historic city center. Today, it is outfitted with faux-Ming-Qing architecture and kitschy gift shops as far as the eye can see. You can drink a Starbucks iced shaken espresso while gazing at Song dynasty ruins, or buy a wanghong Longjing milkshake and traditional mung bean cakes. Tourist shops face as much involution as any other, so they must adopt ever more aggressive marketing tactics to stand out. Classic tactics include free samples and vociferous greeters who shout down passersby. But I was most amused by the staff who sat on stools in front of jewelry shops, loudly banging a piece of metal with a mallet as if silversmithing by hand. The actual products were all mass-produced, of course, but the performance of artisanship was necessary to get customers in the door. The half-hearted hammerers always looked exceptionally bored.

This phenomenon seemed like a microcosm of China’s shifting economy. Dafen Ancient Village in Shenzhen was once known for producing much of the world’s knockoff art—a city of amateur oil-painters churning out Van Gogh dupes at scale. But when we went, it was clear that Dafen was more a tourist destination than anything else. One painter livestreamed on Douyin, while others implored us to take an art lesson ourselves. I wondered how many of the paintings were still exported versus sold to day-trippers like us, here to gawk at non-automated production. Chinese leaders may insist that the real economy is all that matters, but capital incentives push humans toward services, simulacra, and digitization.

In between the top tier cities of Hangzhou and Shanghai, we made a stop in Yuyao, a Zhejiang city of less than 1 million (basically a backwater in Chinese population scales). Empty copy-paste apartment buildings created an awkward gap-toothed skyline. Yuyao is known for an especially high concentration of raw plastics factories, but we had come to visit a precision manufacturing company higher up the value chain.

Rather than climbing up from the bottom, the company started by making a niche product with high technical requirements. It then took Covid as a chance to expand into an odd grab bag of lower-complexity areas. The factory even made their own drills. Like at Tencent, the executive we spoke with seemed more interested in self-sufficiency than gains from trade. With each additional product line, we would ask, “Why did you decide to start making this too?” He always shrugged as if the answer were obvious: “Why not?”

The Western mind cannot comprehend such an “unstrategic” approach. I thought of a conversation in Dan Wang’s Breakneck about how Chinese factories adapted to Covid demand:

“American manufacturers constantly asked themselves whether making masks and cotton swabs was part of their 'core competence.' Most of them decided not." He put down his teacup and looked at me. "Chinese companies decided that making money is their core competence, therefore they go and make masks, or whatever else the market needs.”

I also recalled the Wanfeng airplane factory that I visited last year. There were clear resonances between the two. Symmetrical lines like “Five years ago, this land was chicken coops” and “Ten years ago, this city was just a mountain.” The bosses’ pride in strengthening China’s indigenous manufacturing capacity—not via Nike shoes or cheap plastic toys, but in the high-complexity domains that China previously had to import from Europe and Japan. I don’t want to psychoanalyze too much, but in both cases, I sensed that the Chinese manufacturing boss was hosting us in part to flex on their diaspora friends: Look, this is the new China. Yes, they had to move out of Tier 1 cities to unglamorous industrial towns, giving up a cosmopolitan social scene to work 007 on the factory floor. But this was a mission bigger than themselves. They were the reason Made in China 2025 was real. And that was worth it.

After missing the train (we didn’t qiang tickets fast enough), we asked our Didi driver en route to Shanghai whether he ever considered living there instead. “Shenghuo jiezou tai kuai,” he replied. It’s a common reply you hear from people outside of big cities. The pace of life is too fast.

Youth unemployment rates in China now hover around 20%, though the true numbers are unclear. At lunch, my 24-year-old cousin told me about his college classmate who just got rejected from a job as a low-level airport worker. In this economy, he was not even qualified to push luggage carts around. But my cousin’s own accounting job is not bad. He gets weekends off, and can do overtime from home.

My longtime understanding was that Chinese people do not believe in mental illness. So I was surprised to see a big mental health installation in the middle of a mall. On baby-blue signage, passersby were encouraged to journal feelings of burnout on sticky notes to drop into a plastic box. Therapy-speak slogans prompted visitors to “release toxic negative energy” and “don’t be too hard on yourself”; if feeling angry, you could try releasing it via physical exercise and creative expression. Just like recovering techies in San Francisco, burned out Beijingers have also started creating “third places” and hosting “life-story salons,” writes Chang Che. Aha, I thought. This is a sign of a rich country: China is summiting Maslow’s hierarchy.

However, even leisure devolves into competition. I hear that the Shanghai marathon lottery is impossibly selective, and a popular new museum exhibit showcasing Egyptian sarcophagi just opened a 12am to 6am timeslot after all the others filled up. In a piece for Asterisk Magazine, Chinese Doom Scroll writer Molly Huang describes the trend of “Special Forces Tourism” (特种兵旅游): “maximizing your vacation time to do the absolute most, packing as many as a dozen destinations into one day. A sample itinerary looks like this: You take the overnight train into Beijing. Arriving Saturday morning, you visit Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden Palace, the National Museum, Mao Zedong’s Memorial, the famous Wangfujing shopping area, and a dozen more locations all in one day, quickly taking a photo at each to prove you were there.” Turns out you can 007 your hobbies as well as your job.

In a fascinating conversation on Concurrent, a Chinese investor sums up youth anxiety as follows: “In China, everyone believes the state will ultimately succeed, but no one knows whether they'll be the victor or the price paid for victory.”

Still, Shanghai is as nice as ever. The malls are shinier, the coffee more third-wave. Restaurants have replaced rickety plastic stools on the patios with camping chairs, and some girls are even wearing athleisure (and braving the accompanying tan). Consumer brands like Chagee are embracing guochao aesthetics: a kind of yuppified traditionalism, or “China chic.” My mom laments that several of her favorite hole-in-the-wall neighborhood vendors—the vegetable lady, the jianbing stand—have gotten priced out of their current spots, or replaced with bigger developments. Durians are trendier but less stinky than they used to be—according to my grandparents, the kids can’t handle the real stuff.

Since smartphones are as essential as an ID and wallet, I adopted a clunky solution of carrying around two at all times: my iPhone equipped with a VPN, and a Xiaomi phone to hotspot and complete Chinese phone verifications from. Since I can’t read Chinese, I often find myself stuck in a mini-app while trying to complete checkouts and have to beg for help from a sympathetic bystander. Error messages can be inscrutable. Aadil was never able to set up his WeChat, and perhaps more cruelly, the vending machines refused my facial recognition scans, locking me out of cold water in the humid subway stations. I never felt more like a Luddite.

Customer service is improving as well. It’s as if the businesses all operate by Ray Dalio’s Principles: every interaction prompts you to rate it with smiley face buttons, whether bathroom cleanliness, Didi drivers, customs agents, or food. Gone are the days of waving down indifferent waitstaff at restaurants. Now, eager hostesses dangle free ice cream and beer in return for a Dianping review.3 Grades and ranks don’t stop in college. In modern China, evaluation never ends.

Someone once told me that China is the best place in the world to be a consumer. You can see such innovation shine brightest in the tea-drinking accoutrements: disposable cups for cold-brew that filter out leaves, carrier handles for take-out cups, flavors like Manner’s “osmanthus longjing latte” that actually taste good. Urban hubs feature other exotic conveniences too: battery packs on every block that you can rent for $0.75 an hour and drop off wherever, tiny electric fans to relieve you from 100 degree August days, LED screens in form factors that the West has never seen—building facades, foldable phones, and smart glasses much lighter weight than the Vision Pro. In the Hangzhou spa, we donned pink pajamas; dined on an AYCE buffet of crab, dragonfruit, and coconuts; lay down in camp-themed nap pods; and restored our chakras in Himalayan salt saunas.

For Clara, who had never been to China before, the abundance was mind-boggling. The United States was supposed to be the richest and most developed country in the world. Why did China have so many quality goods that we did not? Why hadn’t such obvious quality of life improvements traversed the Pacific? We bounced around theories. Maybe manufacturing created faster feedback loops, competition forced differentiation, or Chinese consumers were less brand-loyal and more likely to switch for 1.5x better instead of 10x better products. I still don’t know what the answer is, except that we came up with ideas for new import-export schemes roughly three times a day.

Infrastructure, too, might be viewed as consumer surplus. Overcapacity might squeeze EV companies, but it also means buying a new BYD car for less than $10k USD. High-speed rail and clean public restrooms and well-maintained parks all contributed to a sense of ease. In the US, blue state residents pay high taxes without really feeling what the government provides. In China, these daily niceties can’t be ignored. Without other basic freedoms, safety and convenience form the pillars of state legitimacy.

When my parents moved from Shanghai to Duluth, Minnesota for grad school in 1991, America was a no-brainer. “I didn’t think about it that much,” my mom said. “Most of the top university students wanted to go abroad. We were curious to see what was out there. We were on student visas and scholarships, so we didn’t know if we would move long-term.”

“At what point did you decide to stay?”

“Well, we got jobs.”

The economy, cleanliness, schools, and safety. There wasn’t much point in deliberation. Everything was obviously better in the States. (Except the weather, perhaps—in Minnesota it snowed from October to April each year.)

But a country’s trajectory is hard to predict in advance. Over the next decade, China would grow by roughly 10% a year. Markets liberalized, China joined the WTO. GDP per capita soared from $347 in 1990 to $951 in 2000, moving the country into the World Bank’s middle-income category. Many who bought apartments in Shanghai—they were cheap then—saw valuations jump tenfold. These were the boom years. If you were born in the lucky 60s and stayed, it didn’t take much strategizing to ride the wave up. A generation of Chinese went from Cultural Revolution kids to becoming millionaires overnight. Reform and Opening was like the best IPO a country could ask for.

“I don’t regret it, but I sometimes wonder what I’d be doing if I had stayed.”

On our second-to-last day, we met a group of Chinese founders at Mosu Space, a mini office park and coworking space for AI startups. It’s located next to Tencent’s Shanghai office, and on the steps outside, giant block letters spelled out buzzwords like “REASONING,” “INFERENCE,” and “AGI.”

The first nutty thing about Mosu is that it’s 100% funded by the Shanghai and Xuhui District governments, which subsidize not only real estate, but also training data, mentorship, and compute for their portfolio companies. I tried to imagine the San Francisco equivalent—like if Daniel Lurie teamed up with the Hayes Valley Neighborhood Association to pay for hacker houses and GPUs. When we toured the Mosu showroom, we were there concurrently with a group of intimidatingly fashionable Taiwanese influencers. As they vlogged in front of “AI scent diffusers” and an “AI bench press,” I couldn’t help but wonder who sponsored their trip.

Many of the founders attended US universities and worked in Silicon Valley before moving back to China. Returnees are dubbed haigui, a pun on “sea turtle.” I asked why they started companies here, given the scarce capital environment, cutthroat competition, and hostile government policies. VC money has mostly left, and Chinese businesses are notoriously averse to paying for SaaS due to a history of piracy. Hardware I get—one founder said he could replace a robot hand on a 3-day turnaround—but building software startups in China seemed basically insane. One person told me that she had to stop hosting demo days because BAT executives kept showing up to copy creative ideas.

People’s reasons for returning were mixed. For some, it was a business opportunity. Government investments in AI/robotics and DeepSeek mania had rejuvenated the space since the 2021 tech crackdowns. While acknowledging that top research talent was still in the US, multiple people said that the median Chinese engineer was more talented and hardworking, and a top-down strategy may be better for diffusion. For others, it was the lifestyle. Not only family and cultural comfort, but also the aforementioned consumer convenience, public safety, and quality of life. One haigui told me that when she was younger, her Shanghainese friends would ask “Did you come from the countryside?” as an insult if you made a provincial mistake. Now, instead they jab: “Did you just come back from abroad?”

Which is not to say that Chinese founders don’t feel Silicon Valley envy. The dream is still to access money from Western investors and customers instead of the domestic market (this strategy is called chuhai). Folks frequently referenced HeyGen, which took great pains to move from Shenzhen to LA, and Manus, which moved from Beijing to Singapore—both to escape US chip export controls. At the Yuyao factory, I saw the executive’s face light up when I mentioned how much his office resembled that of my old startup, Aeron chairs and all (though these were $30 dupes). And the most popular role models are still American CEOs—especially Elon Musk, whose biography still graces every bookstore bestseller section.

It was hard to recall that just three years prior, Shanghai experienced the worst lockdowns the world has ever seen. People—rich, poor, old, young, sick, healthy—were trapped in cramped apartments and field hospitals for months on end, going outside only to get swabbed before returning indoors. Food was scarce; due to logistical failures, many parents went hungry to feed their kids. Hospitals let patients die rather than diagnose them with Covid and increase the stats. My paternal grandfather was one such case.

But nobody I talked to brought up the lockdowns. The city was alive again, and many residents wanted to move on. I’ve noticed this about Chinese people, my family included: they are remarkably effective compartmentalizers, ruthlessly focused on the here and now. Sad histories are not to be dwelled on. Trauma is suppressed except when motivationally useful (e.g. the century of humiliation and encouraging national self-reliance). It takes a lot of prodding to get anyone to talk. And besides, most individuals don’t feel they had it so bad—when suffering is collective, it is the water you swim in.

The mindset is well-encapsulated in Leslie Chang’s Factory Girls. Published in 2008, it’s a brilliant ethnography of female migrant workers in Dongguan, which is an hour’s drive from Shenzhen. Chang balances a plain account of the brutal working conditions the women face with their immense personal vitality. These women did not view themselves as victims, but rather thick-skinned, strong-headed champions of their own life story:

To come out from home and work in a factory is the hardest thing they have ever done. It is also an adventure. What keeps them in the city is not fear but pride: To return home early is to admit defeat. To go out and stay out—chuqu—is to change your fate. [...]

The migrant women I knew never complained about the unfairness of being a woman. Parents might favor sons over daughters, bosses prefer pretty secretaries, and job ads discriminate openly, but they took all of these injustices in stride—over three years in Dongguan, I never heard a single person express anything like a feminist sentiment. Perhaps they took for granted that life was hard for everyone.

I became endeared to characters like Chunming, who left her village at 16 and became obsessed with self-improvement: switching jobs every few months to double her pay, studying etiquette books on nights and weekends, jumping into a pyramid scheme to give motivational talks to other girls. Or Yixia, who made money teaching factory executives a language she herself barely spoke:

Sometime I feel very tried, but sometime I feel very enrich, she wrote. Her English was still full of mistakes; she was moving too fast to correct herself. But who was I to criticize her? In the two years I had known her, she had gotten exactly what she wanted.

Chinese culture is often described as conformist. But this can suggest a lack of personal ambition, whereas I felt that the individuals I met were some of the “highest agency” in the world. They didn’t focus on how many tariffs Trump levied, or that the state could shut down their startup any time. They knew that competition was tough and unfair, that margins were thin. The only way to survive was to believe—stupidly, irrationally, delusionally—that you might beat the odds.

Even though I’ve never lived in China, people I meet are always encouraging me to “come back.” “Shanghai will always welcome you,” I hear from relatives and strangers alike. Non-Chinese often misunderstand how much “Chinese” describes a people and not a passport (this is the root of much geopolitical strife). Just as my grandmother “returned” to China from Indonesia, where her family resided for generations, there’s a sense that huaren will always be welcomed back, should we choose to move.

My own loyalties are straightforward. I have never lived anywhere but the United States, and my life in San Francisco is very good. The liberty to speak my mind is one of the most precious rights in the world; as such, my values (and livelihood) are fundamentally incompatible with the Chinese state. When my parents dragged me to Shanghai photo studios as a kid, the staff quickly clocked me as American because of how many times I told them “no.”

But for the first time, for an educated Chinese person, the decision to stay or leave does not seem so obvious. At this point, we all know America’s struggles to manage urban cost or crime or infrastructure. What’s more, the United States in 2025 has become hostile to immigrants of all kinds. I can observe from my non-American friends that living here without a passport does not feel very free. International travel, attending protests, writing blogs, switching jobs—these activities are all now fraught with risk. Like the riot gear that lurks menacingly on every corner in Shenzhen, the Trump administration’s high-profile deportations enforce a chilling effect on daily life.

So it is no surprise to see more overseas Chinese returning home. According to a 2023 government report, the number of haigui has increased by 33% since 2018. The main pull factors they cite are daily convenience (54%) and China’s economic outlook (44%), while the push factors are a worsening geopolitical and immigration environment abroad (17% each). For some I spoke with, I sensed that the quality of life gap made them more skeptical of liberal democracy. The Chinese system does stupid things, but so does America, they implied. At least the trains work.

One of the most interesting parts of this trip was spending time with Clara, a self-identified liberal patriot from Los Angeles. I could see her gears turn in real time as she processed her experience. “The system isn’t supposed to work, but it does,” she frequently said, befuddled. I also expect more Silicon Valley elites to start visiting China again this year, which is a good thing: more of us would do well to feel the dissonance firsthand.

For what it’s worth, I don’t actually think that more corporate documentaries and propaganda posters will herald an e/acc victory in the United States. They’re fun, but not the secret to China’s success. Rather, our optimism must derive from seeing material improvements in our everyday lives: cheaper homes, faster transport, safer cities. And that means improving the incentive system for R&D in the US—shaping markets for innovation in the most socially valuable domains, in addition to the places where profits are highest.

Furthermore, we require a competent state to identify and distribute those innovations. In the US, when politicians make campaign promises, I never actually expect them to follow through. But Chinese leaders do—for better and for worse. The 2025 plans to build 1,350 Shenzhen parks or reduce China’s energy dependence aren’t mere propaganda. (Neither, tragically, was the one-child policy.) Accountability is built into China’s bureaucratic system through KPIs, and you can see the results firsthand.4

But citizens in a democracy should care about outcomes, too. As Abundance emphasizes, well-intentioned process is not enough. Clara and I brainstormed about startup-style metrics dashboards for our own city governments. What’s the current GDP of San Francisco? How are we doing on homelessness targets each quarter and year? Let’s keep free and fair elections, but why can’t we have the data to inform our votes?

The alternative scares me. It’s untenable to have such low expectations for our leaders, and young Americans are increasingly blackpilled on their rights—what good is free speech if the government doesn’t respond to citizen concerns? What good is an open internet if it’s spreading misinformation? What good are civil liberties when they seem to trade off with public safety? What good is tolerance if there’s only so much empathy to go around? In my essay on Taiwan, I called this pattern a “democracy doom loop”:

On one side lives our dysfunctional institutions, far more powerful than they are effective. On the other is citizens’ declining faith and interest in democracy itself. Less public interest leads to less competent institutions. Worse institutions further depress citizens’ faith. And so it goes, down the drain.

Otherwise, we may move increasingly toward “authoritarianism without the good parts,” as Dan has taken to saying. Crony capitalism, cultural conservatism, talent competition so intense that it makes Vivek Ramaswamy look like a wimp. Glorifying reckless military expansion. A cult of personality, an autocrat in charge. Crushing the unions and civil society organizations that push back against state power. As Tianyu Fang put it in our podcast from February: “If you've won this technological competition but abandoned all the liberal values that made America America, you're left with nothing. You're left with alt-CCP in the United States of America.”

Overall, my trip was a blast. There are other places in Asia I’d like to visit—Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand—but whenever the opportunity presents itself, I find myself returning to China again and again. Part of this is family ties, part is a preference for depth over breadth. But a substantial component is sheer fascination, and a solipsistic desire to understand China so that I might better understand America and myself.

There’s a saying that goes something like “After one week in China, you feel you could write a book. After one year, you think you could write an article. After ten years, you realize you know nothing.” I am currently in the second stage of hubris, so forgive me for the generalizations I will surely regret. This irreducibility is a function of both China’s size and speed: it’s a country still modernizing at a mind-bending pace, its future still radically undetermined. Shanghai recently surpassed Taipei in my personal city ranking simply because it feels so different on every trip. For the first time, I grokked why someone might cross the Pacific Ocean, then turn back again. Expats there are all addicted to the pace of change; everywhere else is slow in comparison. It’s the same reason I love San Francisco, for all its thorns—China is a place where things actually happen.

I often hear that things are worse now, compared to the golden years of the late 2000s. Politically, it’s true, but it’s hard to leave feeling too pessimistic. Choppy waters train the strongest swimmers. I prefer spending time in places like this: where God-like technologies meet our medieval institutions and Paleolithic emotions. These sites produce the most interesting questions: What does modernization feel like, in your bones? What is it like to live in a place that transforms—physically, culturally, spiritually—at this rate? Are you a surfer cresting a wave, or wiping out on the shore? The hurricanes of progress blow fast and hard. The factory girls had it right. Survival is a process of constant self-reinvention.

final notes

I give 5 stars to all three books mentioned, which all cover China in different ways: Breakneck, Factory Girls, The Rise and Fall of the EAST.

The fun part about traveling with writers is that they’ll likely write up their own reflections. I’m keen to see what others noticed and where we diverge. Sign up for their newsletters to get notified, and in the meantime, check out some of their past posts I liked:

I’m also thinking to make a proper habit of spending 2-3 weeks exploring different parts of China with friends each year (here’s the essay I wrote about my last). My current candidates for next year are Guizhou and Chongqing, but open to other suggestions too!

Thanks for reading,

Jasmine

When used alone, juan is both an adjective and a verb. Your grindsetting coworker who’s always working weekends is juan; if that coworker starts to pressure you to do the same, you might say bie juan wo, or “Don’t pressure me”!

For this reason I try to be forgiving of the delivery scooters that routinely tailgate me and my fellow pedestrians on narrow sidewalks. I often think of this feature on the insane pressure and safety issues that delivery drivers face, translated by Jeffrey Ding’s ChinAI.

Dianping is like Chinese Yelp, but much more widely used. Note that American Yelp, too, is dependent disproportionately on the evaluative labor of Asian women.

From the Yasheng Huang book: “These indicators are broken down into five broad categories—economic development, human capital, quality of life, environmental protection, and key infrastructure—and within each category there are subcategories. For example, economic development comprises six indicators: GDP per capita, share of nonagricultural sectors in GDP, share of services in GDP, contribution of technical progress to GDP, share of trade to GDP, and degree of urbanization. The indicators are weighted, with economic development given the largest weight, at 28 points (out of 100), human capital given 17 points, quality of life 22 points, environmental protection 18 points, and key infrastructure 15 points.”

Well done. Best piece on modern China I have ever read. Thanks for taking us on a profound journey in a fascinating country.

Fantastic! Matches 100% with my experienxe. I've been visiting remote parts of China for 30 years and I know nothing!